빛의 질감이 열어놓은 신성, 영성,

그러므로 어쩌면 인성

고충환(Kho Chunghwan 미술평론)

회광반조, 빛을 돌이켜 거꾸로 비춘다는 뜻, 그러므로 언어나 문자에 의존하지 않고 자기 마음속 영성을 직시하는 것. (선종 불교)

반 입체 형식의 오브제 작업이 빛과 공간에 대한 이야기라고 한다면, 평면 캔버스 작업은 시간의 흔적들이 쌓여가면서 만들어지는 빛이라 할 수 있다...여기서 빛은 절대적인 존재를, 그리고 색은 물질계의 삼라만상을 상징한다...그리고 마침내 화면 속에서 빛을 좇아가는 작업이 결국은 나 자신을 찾아가는 과정임을 깨닫게 되었다. (작가 노트)

태초에 신이 빛을 창조했다. 그러므로 빛이 세상에 가장 먼저 있었다. 그런 만큼 빛은 이후에 올 것들, 이를테면 생명의 씨앗을 상징하고, 존재의 원형을 상징하고, 만물의 근원을 상징한다. 신을 상징하고, 말씀을 상징하고, 로고스를 상징한다. 숨어있으면서 편재하는 신(루시앙 골드만)을 상징한다. 그러나 이처럼 부재하면서 존재하는, 부재를 통해서만 존재하는 신을 어떻게 아는가. 바로 이처럼 신을 알고 표현하는 방법이 타고난 도상학자이며 상징주의자이며 표상 제조공인, 그러므로 어쩌면 신의 사제들인 화가에게 과제로 주어진다. 그리고 화가들은 빛으로 화한 신을 표현하기 위해 후광(님부스)을 발명했고, 스테인드글라스를 발명했다. 그리고 그렇게 중세 이콘화를 통해서, 그리고 천창으로 비치는 장엄하고 부드러운 빛의 질감을 통해서 사람들은 신의 임재를 실감할 수 있었다.

신의 시대가 가고 인간의 시대가 도래했을 때, 그러므로 르네상스 이후 빛은 신을 위한 것이라기보다는 인간을 표현하기 위한, 엄밀하게는 인간의 내면으로 들어온 신, 그러므로 인격의 일부로서의 신성을 표현하고 암시하기 위한 매개체로 주어진다. 특히 바로크미술에서 그런데, 마치 자기 내면으로부터 은근하고 성스러운 빛의 기운이 발하는 것 같은 조르주 드 라투르와 렘브란트, 그리고 빛의 도입으로 극적 긴장감과 함께 마치 파토스의 물화 된 형식을 보는 것 같은 카라바치오의 경우가 그렇다. 그리고 근대 이후 계몽주의와 자연과학의 시대에 빛은 색의 문제로 넘어가는데, 빛과 색의 광학적 상관성에 처음으로 눈뜬 인상파 화가들이 그렇다. 실제로 인상파 화가들은 색을 찾아 빛 속으로 걸어 들어간 최초의 화가들 그러므로 외광파 화가로 불리기도 한다.

그리고 어쩌면 지금도 여전히 그 연장선에 있다고 해도 좋을, 그러므로 재현의 시대 이후 추상의 시대에 그 바통을 색면화파 화가들이 이어받는다. 특히 클레멘테 그린버그와 헤롤드 로젠버그에 의해 지지되는 마크 로스코와 바넷 뉴먼이 그렇다. 각 그린버그로부터 평면성(모더니즘 패러다임에서 회화가 시작되는 근원 그러므로 회화의 그라운드로 보는)을 그리고 로젠버그로부터 숭고의 감정(초월적 존재 감정 그러므로 어쩌면 다시 내면으로 들어온 신성?)을 유산으로 물려받아 정식화한 것인데, 그 유산이 최근 물질주의 이후 그 반대급부로 주목받고 있는 영성주의와 통하고, 크게는 박현주의 작업과도 통한다.

이미 지나쳐온 줄 알았던 신성을 새삼 되불러 온 것이란 점에서 시대의 흐름에 역행하는 것으로 볼 수도 있겠으나, 그보다는 그동안 잊힌 줄 알았던 신성에 다시금 주목하고 각성하는 계기로 보는 것이 타당할 것이다(인간의 한 본성으로서의 신과 신성에 대해서는 인식론적 문제라기보다는 존재론적 문제로 보는 것이 합당하다). 그리고 여기에 재현으로부터 추상으로, 그동안 달라진 문법에도 주목해볼 필요가 있다. 말하자면 추상 자체가 오히려 부재하면서 존재하는, 부재를 통해서만 존재하는 신을 표상하는 전통적인 기획과 방법에 부합하는 면이 있고, 이로써 추상을 통한 현대미술에서 그동안 잠자던 신이 다시 깨어났다고, 그리고 그렇게 신이, 그리고 신성이 진정한 자기표현을 얻고 있다고 해도 좋을 것이다.

그렇게 작가는 빛을 그리고 색을 그린다. 그러므로 빛과 색은 작가에게 소재이면서 어느 정도 그 자체 주제라고 해도 좋을 것이다. 그렇게 빛과 색을 주제로 한 작가의 작업은 크게 입체 조형 작업과 평면 타블로 작업으로 나뉜다. 이처럼 드러나 보이는 형식은 다르지만, 정작 이를 통해 추구하는 의미 내용은 상통한다고 보아 무리가 없을 것이다. 형식적 특성상 입체 조형 작업이 형식논리가 강하다면, 평면작업은 아무래도 그림 자체에 대한 주목도로 인해 상대적으로 의미 내용이 강조되는 점이 다르다고 해야 할까.

먼저 입체 작업을 보면, 주지하다시피 작가의 작업은 벽에 걸린다. 벽에 걸리고, 벽 위로 돌출된다. 일반적인 정도를 넘어서는 상당한 두께를 가진 정방형과 장방형의 변형 틀을 만들고, 그 표면에 대개는 단색조의 색채를 올린다. 그리고 모든 측면, 이를테면 화면의 위아래 부분과 좌우 측면에 금박을 입힌다. 여기서 회화의 전통적 문법인 정면성의 법칙이 소환된다. 우리는 거의 저절로 혹은 반자동으로 그림 앞에 선다. 그림을 정면에서 볼 버릇하는 것이다. 그러므로 적어도 외관상 작가가 봐줬으면 하는 부분은 색채가 올려진 정면 부분이고, 그러므로 금박 처리한 측면 부분은 그저 우연히 눈에 들어오는 편이다. 혹은 그렇게 보이도록 조심스레 계획된 부분이 있다.

그렇게 색이 정면으로 보이고, 빛은 우연히(?) 눈에 들어온다. 간접적으로 보인다고 해야 할까. 간접적으로? 바로 이 부분에 빛의 질감에 대한, 빛의 아우라에 대한, 빛의 울림에 대한 작가의 남다른 감각이 숨어있다. 빛의 진원지 그러므로 광원을 직접적으로 제시하기보다는 간접적으로 제시하는 것이고, 빛을 받은 물체가 그 빛을 되비치는 식으로 제시할 때 빛의 울림이, 빛의 아우라가 오히려 증폭된다고 본 것이다.

그렇게 정작 색도 없고 금박도 없는 벽면에, 조형과 조형 사이의 허공에 빛의 질감이 생긴다(맺힌다?). 그렇게 조형이 만들어준 조형, 조형에서 비롯된 조형, 조형으로 인해 비로소 그리고 겨우 존재하는 조형으로 치자면 그 전형적인 경우가 그림자다. 그렇게 작가의 입체 조형 작업에선 색면이, 빛의 질감이, 그리고 여기에 그림자가 하나로 어우러지면서 상호 간섭하는 형국을 보여준다. 금박과 함께 때로 금분을 사용하기도 하는데, 금박에 비해 더 부드럽고 은근한 빛의 질감을 얻을 수가 있다.

이 일련의 입체 조형 작업에서 결정적인 것은 말할 것도 없이 빛의 질감이 연출해 보이는 특유의 분위기다. 그리고 그 분위기는 우연히 본 빛의 질감에서, 간접적인 빛의 질감에서, 되비치는 빛의 질감에서 유래한다. 그렇게 간접적인 빛, 되비치는 빛, 그리고 우연한 빛의 질감이 신의 알레고리 같다. 빛으로 화한 신의 알레고리 같고, 그럼에도 직면할 수 없는 신(신을 직면하면 눈이 멀거나 몸이 굳는다)의 알레고리 같고, 숨어있으면서 편재하는 신의 알레고리 같다. 그러므로 인간 내면의 신성을 각성하고 영성을 일깨우는 빛의 성소 같다.

그리고 여기에 일련의 타블로 작업이 있다. 입체 조형 작업에 비해 더 내면적이고, 입체와는 다르게 내면적이다. 입체도 그렇지만 특히 타블로 작업에서 작가 회화만의 특장점이랄 수 있는 전통적인 템페라 기법이 유감없이 발휘되고 변용되는 것으로 봐도 좋을 것이다. 생 아사 천에 토끼 아교로 초벌을 한 연후에, 그 위에 호분과 티타늄화이트 그리고 중탕 가열한 토끼 아교 용액을 섞어 만든 젯소로 바탕 작업을 하는데, 그 자체만으로도 이미 회화라고 부를 만한 완성도를 보여주고 있다. 그만큼 과정에 철저한 경우로 보면 되겠다. 그리고 그 위에 금박을 붙이기도 하고 금분을 칠하기도 한다.

그리고 최종적으로 색채를 올리는데, 마치 색 밑에서 부드러운 빛의 질감이 배어 나오는 것 같은, 색 자체가 진즉에 자기의 한 본성으로서 머금고 있던 빛의 잠재적인 성질이 비로소 그 표현을 얻고 있는 것 같은, 색 자체가 은근히 빛을 발하고 있는 것 같은, 그리고 그렇게 빛과 색이 하나인 것 같은 미묘하고 섬세한 분위기가 감지된다. 그리고 그 분위기에 또 다른 분위기가 가세하는데, 가만히 보면 그림 속에 크고 작은 비정형의 얼룩으로 가득하다. 아마도 금분을 칠할 때 더러 흩뿌리기도 했을 것이다. 아니면 때로 채색을 올리는 과정에서 흩뿌리거나. 그리고 그렇게 마치 타시즘에서와도 같은 비정형의 얼룩이 생성되었을 것이고, 그 위에 채색을 올리면서 그 얼룩이 더 두드러져 보이기도 하고, 때로 화면 속으로 침잠하는 것도 같은 은근하고 부드러운 빛의 질감이 연출되었을 것이다.

그렇게 크고 작은 비정형의 얼룩들로 가득한 화면 앞에 서면, 마치 화면 속으로 빨려들 것만 같다. 부드럽고 은근한 빛의 반투명한 깊이 속으로 빨려들 것도 같고, 그 끝을 헤아릴 수 없는 막막한 우주 속을 떠도는 것도 같고, 그 바닥을 알 수 없는 심연을 들여다보는 것도 같고, 마치 신기루와도 같은, 언젠가 어디선가 본 적이 있는 질감의 희미한 기억을 떠올리게 하는 것도 같다. 기억마저 아득한 상처들의 풍경을 보는 것도 같고, 언젠가 설핏 본, 형상은 온데간데없고 다만 그 질감과 색감의 분위기만 남은, 고려 불화의 장엄을 보는 것도 같다.

실제로는 멀리 있는 것인데 마치 눈앞에 있는 것 같은, 실제로는 아득한 것인데 마치 손에 잡힐 것 같은 감정을 발터 벤야민은 아우라라고 불렀다. 그게 뭔가. 그것은 혹 신일지도 모르고, 인간이 자기의 한 본성으로서 간직하고 있는 신성일지도 모르고, 인간 내면의 잊힌 한 풍경일지도 모른다. 그리고 벤야민은 그 아우라가 중세 이콘화 속에 들어있다고 했다. 그렇게 빛의 질감, 빛의 아우라로 형용 되는 작가의 그림은 어쩌면 예술과 종교가, 인성과 신성이 그 경계를 허무는 어떤 지경을 열어놓고 있는지도 모를 일이다.

Divinity, spirituality and thus perhaps humanity, opened by the texture of light.

Kho Chung Hwan, Art Criticism

回光返照 – to illuminate again by reversing the light; and therefore to look directly into one’s inner spirituality without relying on language or sign (Dhyāna Buddhism).

“If I am to say that the semi three-dimensional works of objet art were a narrative of light and space, the plane canvas works are light as a result of temporal flow […] Light here signifies an absolute entity, and color signifies the entirety of what composes the material world […] And finally I have realized that to pursue light in the screen is a journey towards the discovery of myself. (Artist’s Note, June 2022)

At dawn of the world, God created light. Hence light preceded every existence in the world. It is, therefore, natural that light symbolizes what would come next, say, the seed of life, the archetype of existence and the origin of everything. It symbolizes God, His words and logos. It symbolizes ‘the hidden God’ that is ubiquitous (Lucien Goldmann). But how exactly do we come to understand God that is absent and existent, and He who exists only through absence? Such a question becomes the main assignment of the artists who are natural iconographers who know God and are endowed with His expression; are symbolists and the producers of representations; who, therefore, should be regarded as the priests of God. The artists have invented nimbus (the light that is drawn behind saints) to better convey the holiness of God, and have invented stained glass. And through such medieval icon painting, and through the solemn yet soft texture of the light through the sky window people could experience the presence of God.

But when the age of God gave way to the age of human, as in post-Renaissance, light too gained a new status as a medium of expressing humans (strictly speaking, to express the divinity that has entered human existence and to imply God’s presence as part of humanity). This is particularly so in Baroque art, with the exemplars of Georges de La Tour and Rembrandt whose paintings depict the subtle and holy light emanating from the inner part of self, and in case of Caravaggio whose works illustrate a dramatic tension and mimic the reified form of painting and pathos by the inclusion of light.

And ever since the world saw the Enlightenment and the advancement of natural sciences, light became the problem of color, which can be witnessed in the works of impressionists who were the first to recognize the optic relationship between light and color. In fact, the impressionists are the first artists to have walked into the light in search of color, and that is where they earned the name of “plein air painters”.

And the Art Field painters follow in the trail of light in the age of abstraction that followed the age of representation, which can perhaps be regarded as the continuum that persists today. Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, who are supported by the critics Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg, fall under such category in particular. Rothko and Newman have, respectively, inherited the ‘planeness’ (the origin where painting begins in the modernist paradigm, as a ground of painting, so to speak) by Greenberg and the emotion of nobility (the emotion of a transcendental entity, therefore perhaps denoting the divinity that returned to inner parts of humanity) by Rosenberg and such legacy has some certain connection to Spiritualist Art which has recently risen as an antagonistic movement against materialism, and in a bigger scale, corresponds to Hyunjoo Park’s works.

It is viable to interpret her works as untimely, as the works have re-conjured divinity that we regard as obsolete, but it is more valid, it seems, to view her works as the cornerstone to revisit divinity that has once thought to be forgotten (it is more valid to look at God and divinity as part of human instinct ontologically rather than epistemologically). And here lies the need to attend to the change in the artistic grammar, from representation to abstraction. Abstraction itself, so to speak, corresponds to the traditional methodology of expressing God that is absent but existent, and who exists only through absence. And therefore perhaps we could safely argue that the sleeping God in contemporary art has awaken through abstraction, and in so doing God and the divinity are achieving their true self-expression.

And so the artist draws light and color. Light and color, then, are not only objects for the artist but the theme itself. The artist’s work that thematizes light and color thereby bifurcates to the three-dimensional plastic art and plane tableau art. We should understand the signification pursued stays intact despite the variegated formats. Perhaps the only difference is that, due to formal characteristics, three-dimensional plastic art displays and relies on formal logic more heavily whereas plane tableau art helps the audience to focus more on the meaning of the art due to the attention given to the painting itself.

Examining the three-dimensional plastic art first, as per her request, the artist’s works hang on the wall. They are hung and become a dent on the wall. The artist forges a square and/or rectangular alternate frame with abnormal thickness and paints the surface with a monotone color. And all sides, for example, the top and bottom part of the frame of the screen and the left and right part, are gold foiled. Here we see the frontality principle in play, which is the traditional grammar of painting. We stand in front of the painting almost automatically due to our habitual use of perspective. The artist seems to have meticulously planned the use of our habit: the part that the artist wants us to see is the frontal part with the color, and the gold foiled sides are merely supplementary.

Hence the color is viewed frontally, and light enters the vision accidentally. We could say that the light is seen indirectly. It is precisely with this indirectness where the artist’s outstanding sensibility towards the texture, the aura and the reverberation of light resides. Instead of directly visualizing the light source, the artist employs indirectness; in so doing, the reflection of light from the object that received the light will amplify the reverberation and aura of light.

Such is how the texture of light is manifested in the void between plastic art and plastic art, and on an empty wall with no color and no gold foil. The exemplar of the phenomenon of plastic art that the other plastic art produces, the plastic art that originated from another plastic art, that which barely exists only because of another plastic art’s presence is shadow. We find an intertwined affair of the colored field, the texture of light and the shadow in Hyunjoo Park’s artworks. The artist sometimes employs gold powder along with the gold foil, which gives a softer and subtler texture of light compared to the foil.

The unique ambience produced by the texture of light is the most decisive appeal from the series of three-dimensional plastic art process. And the ambience originates from the texture of light seen accidentally, from the indirect texture of light, and from the texture of light that reflects. Such types of textures of lights, indirect, reflective and accidental, seem like an allegory of God. They seem like an allegory of God that illuminates through light, God that despite such illumination cannot be directly seen (if you see God directly you either go blind or get petrified), and God that is hidden but ubiquitous. In a way, therefore, they feel like a sanctuary of light that enlightens the spirituality and awakens the inner divinity.

It is here where a series of tableau works lie. The works are more inward than the three-dimensional plastic art work, and the tableau is more deeply internal than the three-dimension. We can see in her tableau works where the artist’s traditional tempera technique (her most impressive strength) really starts to fortify and edify its presence. After laminating the linen with rabbit glue, the artist works on the Ba-tang with gesso made from a mixture of whitener, titanium white and rabbit glue solution that has been double boiled, and the completeness of this sole process qualifies to be called art already. That is how much the artist prioritizes the process. She then gold foils the Ba-tang or sprays gold powder on it.

And in the final step she colors the canvas and the subtle yet sensitive ambience where light and color merges is achieved through the light where its soft texture permeates from underneath the color, where the potential property of light that the color has been inherently endowed with is finally finding its own language, and where color itself seems to emanate light of its own. And another prevailing ambience overlaps on the forementioned ambience; upon close examination we see the drawing is full of atypical stains of all sizes. Perhaps the artist spread the gold powder at will, or spread the paint as she pleased. And the atypical stains probably came to existence through such an act, like tachisme; and by painting on top of the stain the stain sometimes becomes more accentuated, or produces a subtle and soft texture of light as if the stain sank down beneath the surface of the canvas.

Standing in front of the canvas full of various, atypical stains, we feel as though we are about to get pulled into the screen. We feel as though we will get sucked into the opaque depth of the soft and subtle light, and as though we are meandering around the seemingly endless and interminable universe, and as if we are looking into the fathomless depth of the abyss, and as though we are reminded of the déjà vu and involuntary memory that confuses us with its perceived familiarity. It feels as though we are glancing over the scene of scars that no memory can hold or looking at the majesty of Koryo Buddhist painting whose form has etiolated, leaving only the texture and the ambience of the color behind.

Walter Benjamin called the emotion that is distant but feels close, that which is far away but feels palpable as “aura”. What is aura? It may be a God, may be a divinity that men possess as part of their instinct, or a forgotten scenery inside us. Benjamin famously said that such an aura resides in medieval icon paintings. The artist’s paintings, describable as the texture of light and the aura of light, perhaps open up a possibility of transgressing the boundary between art and religion, and humanity and divinity.

색에서 빛으로: 박현주 전

한주연 (미술학 박사,미술비평)

작가 박현주는 이번 전시에서 그동안 추구해온 ‘빛 시리즈’의 연장선장에서 회화와 오브제, 드로잉 등 다양한 형태의 신작을 선보인다. 일본 동경예술대학에서 유화재료기법을 전공하던 작가는 재학 시절 중세 성화의 금빛 아우라에 매료되어 이후 세속적 공간과 성스러운 공간의 경계를 넘어서는 찬란한 빛의 공간을 재현하고자 노력해왔다.

오랜 시간 장인적인 작업의 결과물이며 형식과 일루젼의 통상적 개념을 허무는 그의 작품은 이번 전시에 이르러 더욱 원숙해진 동시에 보다 자유로운 표현과 유희를 반영한다는 점에서 어떤 전환점을 맞이한다.

박현주 작가의 작품은 회화와 입체의 실험이나 미니멀리즘에 근거한 즉물적 오브제의 구현으로 볼 수도 있겠지만 그보다는 본질적인 삶에서 연유한 질문과 그의 추구라는 개인적 성찰의 여정에서 비롯된 것이다. 본인의 삶의 무게와 각 고비마다 도사리고 있는 희노애락의 순간들을 빛이라는 가장 근원적인 요소의 조형적 구현을 통해 끊임없이 되새기는 동시에 빛이 던져주는 구원과 치유의 의미를 담아내고자 고분분투 해왔던 작가의 여정이 이번 전시에서도 진솔하게 드러난다.

불완전과 비움으로부터 구원에 이르는 빛

박현주 작가의 작업은 평면 회화 위에서 관념적인 빛의 실재를 재현하는 데서 시작했다. 빛이라는 것은 스스로 완전무결하고 통합된 아름다움의 극치이기 때문에 그를 재현해 낸다는 것은 그에게 막연한 기대와 고된 노동의 연속이었을 것이다. 나 자신의 색과 빛을 인식하기 전 빛은 실제 하는 것이 아닌 어두운 곳에서 멀리 보이는 어떤 것이기 때문에 그의 작품은 추상의 형상에서 출발할 수밖에 없었다.

수많은 형식적 실험과 숙련을 통해 작가는 템페라가 주는 색채의 풍부함과 금박이 만들어내는 빛의 환영을 조화시켜 그 자체가 발광하는 듯한, ‘빛을 입은’ 오브제를 창조해낸다.

원래 색이란 인간의 시각에 속하는 것이며 빛은 신에게 속한 것이기 때문에 서로 대치되는 어떤 것이지만 오브제는 현실의 색과 금박의 환영을 조화시킴으로써 동시에 스스로 빛을 내는 발광체이자 그 빛이 조명되는 반영체가 된다.

그의 작품이 완전무결함과 이성적인 질서가 반영된 조형성을 보여주고 있음에도 불완전과 풍부한 감성의 요소를 내포하고 있는 것은 현실과 비현실, 성과 속을 조화시키고자 하는 그의 의도와 그 자신의 고뇌와 갈등까지도 여과 없이 투영해온 작가의 의지에서 비롯된다. 즉, 보나벤튜라의 말처럼 불완전한 결핍의 존재에서 ‘스스로 빛에 참여하는 정도에 따라 존엄성과 진리를 획득하는’ 과정을 거쳐 그 자체로 빛의 실체를 회복하는 과정을 여실히 보여주고 있다.

반영과 포용의 공간

빛은 대상을 조명함과 동시에 공간을 창조해낸다. 그의 빛 또한 평면 회화이거나 입체 오브제거나 상관없이 빛 자체인 동시에 빛이 투영해 내는 공간의 재현이다. 작가 자신이 오브제에 조명을 비추는 행위를 ‘자신의 내면세계에 빛을 비추는 자아 성찰의 행위’라고 표현했듯이 전시장의 오브제는 깊고 무한한 공간을 응축한 채 이중, 삼중, 사중의 그림자를 드리운다.

특이할 만 한 점은 그의 오브제 작품들이 그 자체의 유닛들을 서로 반사하는 동시에 주변 사물들의 그림자들과 청각적, 촉각적 요소들까지 예민하게 반영한다는 것이다. 그의 작품은 극도로 절제된 형태로 표현되어 있으나 작업의 과정에서 실리는 수많은 반복의 공력과 재질 표면의 미묘한 광택과 색채는 시각 요소 외에도 다른 감각들을 예민하게 한다.

또 한 가지 거기다 더해 공간의 정서적 특징이 이 예민해진 감각들을 흡수하고 관객 스스로가 자신을 비춰볼 수 있는 반영의 특징을 만들어 내고 있다. 이 공간은 박현주 작가 자신이 그러하듯 누구에게 강권하지 않는 비움의 공간이다.

흔히 ‘공(空)사상’이나 ‘무아(無我)’로 일컬어지는 끝없는 자기 비움의 과정은 조형적 구현 과정에서도 볼 수 있을 뿐만 아니라 작품에 대한 작가 자신의 정신적, 육체적 헌신의 태도에서도 드러난다. 이에 더하여 작품의 공간이 극도로 세련된 미학적 구성과 색채를 사용하고 있음에도 그 어떤 주위 사물과 요소도 배제하지 않고 포용하는 것은 그의 삶에서 비롯된 무게와 감성이 실리기 때문이다.

빛의 유희

이번 전시에서 가장 두드러진 특징은 오브제와 평면 회화에서 자유롭고 과감한 유희적 표현이 드러난다는 것이다. 풍부하고 강한 색채와 대담한 구성 양식에도 불구하고 항상 절제되고 숙연한 표현으로 일관해왔던 작가는 오브제에서도 강한 색채를 사선으로 배치하고 평면에서도 작업 과정이 노출되는 표현의 변화를 보인다.

회화에서 도형과 개체의 반복에서 시작하여 최근 동일한 오브제 유닛의 반복적인 배치까지 반복성과 완결성은 일본 유학 시절 작품부터 보여 지던 공통적인 표현 방식이었다.

반복적 행위는 삶의 부정적 요소를 능동적으로 제어하려는 자아의 시도이자 주도권을 회복하려는 주체의 의지로 나타난다. 우리 삶의 근원적인 모습자체가 어찌 보면 반복적 행위로 일관된다고도 볼 수 있듯이 그것을 현재에도 끝없이 되풀이 하는 것은 한편으로는 강박적으로 보일 수 있지만 솔직한 삶의 의지의 표현이다.

유학시절 초기 흑연 작업에서 보여 지는 동그란 도형의 반복은 생명체 내부 깊숙이 내재된 생명 에너지임과 동시에 삶 속에서 정진하는 그의 행위를 반영한다. 어디엔가 있을 생명의 흔적을 계속 찾아가는 작가 자신의 실존적 흔적인 것이다.

이 반복적 행위가 지속되면 거기서는 미세한 차이와 의미가 자체적으로 형성된다. 유희하는 자는 물질과 형식, 삶과 죽음, 심각함과 즐거움, 이성과 감성 등의 양 극단의 요소들 사이를 왕복하고 반복하는 자신의 모습 속에서 놀이의 경우에는 매번 새로운 재미와 경험을, 예술작품의 경우에는 창의적이고 독특한 의미를 찾아가기 마련이다. 작가는 작업에 매진하는 자신의 작업 인생을 통해 점진적으로 해방과 유희적 의미를 발견해 낸 것 같다.

초기 오브제 작업이 엄숙한 기도의 느낌을 주고 있다면 근래의 입체 작업과 회화 작업은 빛으로 인해 빚어지는 형상과 그림자들이 공간에 따라, 주위 사물들의 운용에 따라 더욱 섬세하면서도 자유로운 행동의 반경을 보여주고 있다. 색채와 빛의 경계는 모호해지고 때로는 색 자체가 빛을 머금은 느낌을 준다.

지향하는 빛은 어떤 의도와 의식의 한계로 규정되는 것이 아니며 인간의 감수성마저 그러하다는 것을 형식과 표현의 파격을 통해 작가는 보여주고 있다.

박현주 작가의 전시를 보는 관객들은 구원의 빛이자 자유로움의 빛을 공유하고 작가 인생의 여정을 함께하고 있는 셈이다.

<From Color to Light: Park Hyun Joo>

Park Hyun Joo presents various new works such as paintings, objects, and drawings in this exhibition, as an extension of 'Light Series' that she has pursued. The artist was attracted to the golden aura of medieval icon when she was studying oil painting techniques at Tokyo University of Arts in Japan. Since then, she has tried to recreate brilliant space of light beyond the boundary between secular and sacred space.

Her work, which is the product of long-time craft work and collapses the usual concepts of form and illusion, is at a turning point in this exhibition, demonstrating artistic maturity as well as reflecting freer expression and amusement.

Park’s work is a presentation of a literal object based on minimalism or experiments of paintings and sculptures. Essentially, however, her work is based on questions stemming from the quintessential life and the journey of the artist contemplating the questions. This exhibition reveals her struggling journey throughout which her life's weight and the moments of various emotions have been ruminated on in the formative realization of the most fundamental element, light, and reinterpreted by the salvation and healing of light.

Light: From Imperfection and Emptiness to Salvation

Park’s work began with realizing the existence of ideational light onto plane paintings. Regarding that light itself is the ultimate beauty of faultlessness and integrity, realization of the light might have been repeated experiences of abstract expectation and hard work. Before being recognized as its own color and brightness, light is not something real but something that is seen far away from the darkness; therefore, her work had to start from an abstract form.

Through numerous formal experiments and skill practices, the artist combines the abundance of color produced by tempera and the illusion of light produced by gold-gilding, to create luminous objects ‘wearing light.’

The color and the light are contrasting concepts since the color belongs to the human vision and the light the gods, but the objects, which combine the reality of color and the illusion of gold-gilding, become both illuminating and reflecting bodies.

Although her works show formativeness that reflects complete perfection and rational order, they also deliver incomplete and rich elements of emotion since she intends to achieve harmony between the real and the unreal or between the secular and the sacred and to project her own anguishes and conflicts unfiltered. That is, her works demonstrate the process in which the imperfect existence of deficiency regains its substantiality in light, as Saint Bonaventure said, “acquiring dignity and truth according to the degree of participation in the light.”

Space of Reflection and Embracement

Light illuminates objects and creates space as well. Her light is also, whether it is on a flat painting or a stereoscopic object, a representation of the space projected by the light as well as the light itself. The artist defines the act of illuminating an object as ‘the act of self-reflection shedding light on her inner world.' Analogously, the objects in the exhibition concentrate deep and infinite space and cast shadows of double, triple, and quadruple layers.

It is notable that her objects have their own units reflect one another, while mirroring audial and tactile elements of other neighboring objects. Her works are expressed in extremely modest forms, but the other senses than visual ones get acute by the repeated endeavors in the process of work and the subtle luster and color of the surface.

In addition, the emotional features of space absorb these acute senses and allow viewers to reflect on themselves. This space of emptiness does not govern anyone, neither does Park.

The process of endless self-emptying, which is often referred to as ‘voidness thought’ or ‘selflessness,’ is revealed not only in the process of stereoscopic realization but also in the attitude of the artist's mental and physical devotion to the work. Moreover, her works embrace any surrounding objects and elements although the spaces of the works use extremely aesthetic compositions and colors: this is because the works carry the weight and emotions of her life.

박현주 작업에 관하여; 암시(暗示, allusion)

김대신(미술과 문화비평)

작업은 “회화는 무엇인가?”에서 출발한다. 그린다는 것은 대상, 빛, 본질과 같은 근본적인 물음을 담고 있다. 더불어 작가에게 삶의 의미는 작업의 문제와 연결되어 있다. 회화의 문제에서 출발한 작가의 존재론적 사유는 지속적이다. 작업의 과정은 삶을 성찰하는 과정이며 삶의 의미가 녹아있다. 작업과 삶을 주체적으로 사유하며 전개한다. “어디서 와서 어디로 가는가?” 작가는 생의 근본적인 질문의 해답을 작업에서 찾는다.

삶을 회의(懷疑)한다. 작가의 화면은 삶의 존재적 성찰로 ‘내면의 풀리지 않는 응어리’와 ‘막다른 골목에 선 인간’의 실존적 한계를 담고 있다. 그리고 그리움을 시각화하고 자연으로부터 영감을 얻어 <변형된 생명체metamorphosis>를 1996년에 발표한다. 식물과 씨앗과 같은 변형된 생명체를 나타내던 검은 점은 선에서 면으로 확장한다. 작업의 재료인 흑연의 반사면은 성상화 연구에서 경험한 금박의 반사면과 닮아 있다. 작가는 두 반사면에서 환영의 시각적 효과와 빛 자체가 화면에 안에 있음을 확인한다. 반사 빛이 만든 미지의 시각적 환영을 바라보는 것은 매혹의 순간이다. 작가는 자신을 매혹하는 반사된 빛의 세계를 생명체 내부에 잠재된 생명 에너지의 암시(allusion)로 해석한다.

작가가 집중하는 빛의 반사는 숭고한 아름다움을 간직하고 있다. 비잔틴 이콘(Icon)이나 르네상스 성상화(聖像畵)의 황금빛 배경은 천국의 영원성과 신성한 공간을 상징한다. 작가는 프라 안젤리코(Fra Angelico, 1395-1455)의 감실(Tabernacle) 제단화 <리나이올리 성모자상Linaioli Madonna> 연구에서 금박기법을 체득한다. 금박기법은 간접적으로 드러나는 빛의 반사가 만드는 신비한 아름다움을 창출한다. 금빛 아우라(aura)가 담긴 반사는 물리적 현상과 심리적인 현상을 동반한다. 금박의 반사를 활용한 작업은 새로운 공간의 확장에 주목하며 설치작업으로 이어진다. 작가는 보는 거리, 각도, 조명의 상황에 따라 변화하는 작품을 공간 안에 들어가 감상자가 다양한 시점에서 체험하기를 기대한다. 눈으로 읽는 것과 읽히지 않는 것 사이에 있는 중간 상태에 집중한다. 작가는 입자와 파동의 성질을 가진 빛의 물리적 현상 너머 그리고 표면의 물성 위에 부유하듯 흐르는 추상적인 것을 포착한다. 작업은 추상적이며 은유적인 아름다움과 존재 너머의 신비한 경험을 포함한 무한의 것을 표현하는 것이다.

성상화(聖像畵) 제작 연구를 심화한 작업 <빛으로부터Inner Light>은 자기성찰과 물성에 관한 표현을 동반한다. 성상화는 금박과 템페라로 화면을 나누어 제작한다. 두 기법의 경계는 무한의 신성과 유한의 인성, 금박의 물성과 회화의 평면성으로 조형의 독자적인 창작 방법론을 작가에게 제공한다. 화면 속에 경계를 이루는 금박의 물질성과 템페라의 채색은 박현주 작업의 열쇠이다. 작가의 조형세계는 평면과 입체, 물성과 상징성 그리고 반사와 환영의 관계를 파악하고 확장한다. <변형된 생명체>에서 유기적 생명체의 형상을 제거한 연작 <빛으로부터>는 회화의 ‘평면성(a plane surface)’과 ‘빛의 반사’에 초점을 맞춘다. 작가는 평면성과 빛의 반사를 하나의 주제로 다루며 ‘회화적 오브제Plane Object’라고 부른다. 회화의 평면성과 빛의 반사를 함께 표현한 독자적인 조형론을 펼친다. 전통적인 회화의 평면성을 해체하고 텅 빈 표면 앞에 작가는 자신을 돌아본다. 반사 빛이 사물의 표면에서 벗어나 만든 신비한 환영의 공간을 재현한다. 작업은 회화 안에서 물성을 다룬다. 육면체의 네 측면에 금박을 입힌 ‘회화적 오브제’는 놓이는 공간과 빛의 관계에 따라 가변적으로 작동한다. ‘회화적 오브제’는 빛을 받으면서 사물이 가지는 물성을 상실하고 평면화된다. 지지대와 바탕칠 그리고 물감층이 하나의 물질적인 구조로 미묘한 색다른 공간을 연출한다.

작가는 남산골로 작업실을 옮긴 후 숲길을 걷는다. 소나무와 더불어 다양한 나무의 기운을 받고 나무의 정령을 체감하며 명상한다. 작가는 개념을 끄집어내는 것이 아니라 무의식적인 생각을 없애려고 한다. 작업의 태도는 명상의 태도와 닮아있다. 작가와 작품은 작업과정에서 주체와 객체로 서로 교차하며 만난다. 주체로서의 작가와 대상으로서 작품이 서로 영향을 주고받으며 어느 순간 하나 됨을 확인한다. 특히 금박으로 작업을 진행하던 과정은 시공간 속으로 주체와 객체가 녹아 사라짐을 체험한다. 인식의 주체와 객체 사이의 경계가 무너진 지점에 박현주의 ‘회화적 오브제’가 자리한다. ‘회화적 오브제’는 회화의 평면이 창출하는 자아의 은유(metaphor)이다. 물성이 사라진 캔버스는 물질과 정신의 경계에서 ‘자아의 은유’를 상징하는 새로운 개체로 탈바꿈한다. 즉, 하나의 단위(unit)를 만든다. 몇 개의 단위로 구성된 ‘회화적 오브제’는 반복적으로 벽면에 설치된다.

작품은 자아의 투영이다. 작업은 자기 얼굴을 비추는 거울과 같다. 한 발짝 뒤로 물러선 거리에서 자기를 바로 보게 한다. 작가는 평면을 오브제로 만들어 대상화(objectify)한다. 오브제의 의미는 작가에게 객체이며 대상이다. 기존의 회화 작품을 지지대, 바탕칠 그리고 물감층이 하나의 물질적인 구조로 파악한다. 사각형 캔버스의 측면을 넓혀 육면체라는 구체적인 오브제로 변환하여 ‘회화적 오브제’를 만든다. 일정한 거리를 두고 주체인 작가와 대상인 작품을 동일 선상에 놓고 본다. 작가 자신과 작품을 대상화하는 과정은 세계가 전체로서 하나임을 인식하는 방편이다. 박현주의 작업은 작가와 대상 사이에 간극을 너머 일체화된 관계를 보여준다. 주체와 객체의 경계선 허물기이며 서로의 만남이다.

빛은 존재를 반사한다. 박현주의 작업은 물질 너머의 존재를 암시한다. ‘회화적 오브제’는 현실과 비현실, 물질과 정신, 주체와 객체의 불협화음에서 생명에너지가 가득한 조화를 소망한다. 빛의 반사를 담아 전체로서 하나인 조형의 세계를 기대하며 삶의 무게를 덜어줄 위로의 세계를 제안한다. 빛의 환영이 만든 아우라의 세계는 스스로 그러한 자연스러운 모습으로 함께 마주한다.

김대신(미술과 문화비평)

The artist’s work starts from “What is painting?” Painting includes fundamental questions about the object, light and the essence. Furthermore, the meaning of life in the eyes of the artist is related to her work. Her ontological deliberation about painting is continuous. The process of work is a process of introspecting life and it includes the meaning of life. The artist ponders about her work and life in an autonomous way. “Where do we come from and where do we go?” Park seeks the answer to that query by her work.

Park doubts about life. The artworks represent the feeling of resentment and the feeling of helplessness found through the existential retrospection of life. The artist also visualized longing and got inspirations from nature, and exposed Metamorphosis in 1996. A black spot that represents metamorphosis like a seed and plant expands into a line and into a plane. The reflective surface of graphite resembles with the reflective surface of gilt religious paintings. The artist believes that the visual effects of the illusion of these two reflective surfaces and the light itself are inside the painting. Contemplating the visual illusion made by the reflective surface is a moment of fascination. The artist interprets this fascinating world of reflected light as an allusion of life energy.

The reflection of light which the artist is focusing on preserves a sublime beauty. The golden backgrounds of Byzantine Icon or religious Renaissance paintings symbolize the eternity of paradise and the holiness of the place. Park acquired the skills of gilding by the tabernacle <Linaioli Madonna> of Fra Angelico. Gilding creates a numinous beauty through the reflection of light. The golden aura inside the reflection has a physical and psychological effect. The work using gilding’s reflection is focusing on the expansion of new space and is connected to installation art. The artist expects the viewer to enter inside the space and experience artworks that change depending on the distance, angle and lighting. Park focuses on the intermediate state between the visible and the invisible. Park captures beyond the physical phenomenon of light, which has wave-particle duality and captures the abstractness that float upon the surface of its properties. Her work is abstract and represents the infinity comprising the experience beyond the metaphorical beauty and the existence.

The deeper study about religious paintings <Bicheurobuteo, Inner Light> accompanies introspection and representation of properties. The gilding part and the tempera part of religious paintings are divided during the painting process. The limit between the two techniques, with the infinite divinity and the finite humanity, the properties of the golden leaf and the flatness of the painting, offers the artist an independent way of artistic creation. The key of Park’s work is the boundary between the property of the gold leaf and the tempera painting. The plastic arts of the artist understands the relation between the plane and the cubic world, the properties and the symbolism, the reflection and the illusion, and expands it. The series <Bicheurobuteo>, which excludes organisms from <Metamorphosis>, focuses on the painting’s plane and the reflection of light. The artist treats planarity and reflection of light as a theme. It is called 'Plane Object'. She unveils her own formative theory expressing both the planarity of the painting and the reflection of the light. The artist dismantles the planarity of the traditional painting and self-reflects in front of a blank surface. The reflected light reproduces the space of a mysterious illusion made when getting out of the surface of the object. Her work deals with properties inside painting. The gilt ‘Plane Object ’, a cuboid with four gilt sides, varies with space and light. ‘Plane Object ’ becomes a plane by receiving light, and therefore losing the properties it originally had. With a structure where support, background and the upper layer covered with paint form one material thing it creates a subtle and original space.

Park often strolls down a path in the woods after moving her workroom to Namsan-gol. Receiving the energy from pine trees and other various trees, she feels the spirits of trees as she meditates. She does not intentionally struggle for ideas, but tries to delete unconscious thoughts. Her attitude about artwork is similar to a meditative attitude. The artist and the artwork cross each other as subject and object in the work process. The artist as a subject and the artwork as an object interact together to be united together. Particularly, the gilding process is an experience where the subject and the object become one into space and time. Where the boundary between the subject of perception and the object has disappeared, stand Park’s ‘Plane Object ’. ‘Plane Object’ are the self’s metaphor created by the painting’s surface. The canvas deprived of its properties on the boundary between matter and mind becomes a new object that symbolizes the self’s metaphor. Therefore it forms one unit. ‘Plane Object ’ consisting of several units are repetitively installed on the wall.

The artwork is the projection of the self. It is like a mirror reflecting one’s own face. The viewer has to look at itself objectively from a certain distance. The artist transforms the plane into an object and objectifies it. To the artist, the meaning of the object in art is an object and stuff. She understands existing paintings as material structures with support, background and the upper layer covered with paint united together. By broadening the scope of her work, she moves beyond the canvas to a specific object, a cuboid, to make ‘Plane Objects’. She places the subject, which is the artist and the object which is the artwork in line and keep a certain distance between them. The process of objectifying herself and the object is a way to perceive that the world is one as a whole. Park’s work surpasses the gap between the artist and the object and shows a unity of the two. It is a collapse of the boundary between the subject and the object and is a meeting of them.

Light reflects existence. Park’s work implies the existence beyond substance. ‘Plane Objects ’ pursues a harmony full of life energy inside the disharmony between reality and the unreality, the matter and the esprit, the subject and the object. It proposes a world of consolation by keeping light reflection and expects an artistic world with one as a whole. The world of aura made by optical illusions faces the artist and the viewer naturally by itself.

Daesin KIM (Art and cultural critic)

About Park’s work ; allusion

Daesin KIM (Art and cultural critic)

05. 16. - 05. 30. 2016

Opening Reception: Monday 05. 16. 2016 6 - 8 pm

Mon - Thurs 12 - 6 pm, Sat 10 - 03 pm, Fri - Sun closed

TENRI 天理 cultural institute of New York

43A West 13th street NY NY10011

212-645-2800

www.tenri.org

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

Tenri Cultural Institute, New York proudly presents Hyunjoo Park: The Light of Reason an exhibition from May 16th through May 30th, 2016 with an Opening Reception on May 16th from 6-8PM.

Park’s images have to do with light, so her critics tell us. But they can also discuss in terms of the post-minimalist aesthetic that in its pure form interacts with the viewer. Park’s pieces are site-specific incorporating the gallery space within her them. The shadows caused when installing the boxlike pieces on the white walls, create secondary patterns. In fact, the shadows in Nirvana 3, 2015, (13.8×6×6” each block), appear to be solid and discrete pieces in themselves added to the rectangular sculptures. These results in a figure ground ambiguity that can be discussed in terms of Gestalt psychology that shows us the way we as humans group parts in order to understand them and the way we separate solid and void whose reading has to do with the law of simplicity. By keeping her volumes to the simplest possible geometric forms Park engages in the interplay not only of solid and void but also in 2 and 3 dimensional space. Echoes of Victor Vasarely’s Op-Art seem to be making their way into Hyunjoo’s works too. Vasarely, the father of this style through his 1960s and 70s work influenced a whole generation of artists continuing his kinetic visual experiments and transforming the flat surface into endless possibilities.

In continuing this track Park’s work like Vasarely’s 50s pieces and statements, also has a technological element to it. She sprays rectangular or circular pieces with the paint gun thus creating with mechanical means while referencing the idea of light through her use of nuanced color shading. In his efforts to bring art within everyone’s reach Vasarely used new technologies and in his statements predicted an art that could be projected anywhere in the world within two days thereby removing the work’s aura or singular authority. Park’s modular pieces speak to the idea of reproduction in the mechanical age that recalls the words of Walter Benjamin who wrote about the work’s aura in his “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” He stated that “when the mysticism of originality is removed, everyone can enjoy art.” This tendency was also present in Duchamp’s unconventional and unprecedented Readymades that moved the importance of the artwork from the object itself to the idea of the artist. Like Duchamp, Park provokes the viewer to think by questioning the most basic values of conventional artmaking.

Post-minimalism is process oriented art with site specific aspects and can be varied or continue the minimalist interest in abstraction and mechanically based art. As seen by her Light and Monad series, of 2015 and in their modular nature, Park’s sculptures fit into this vein. But, Park activates another idea as well, one that has personal meaning, one that she describes best in her own words “I wonder what we get out of such an incomplete and ambiguous grind that we call life …. Then finally I realized that by the work I do – that is, tracing light on canvas – I was actually in the process of finding myself.”

FOR MORE INFORMATION:

Please contact Tenri Cultural Institute at 212.645.2800 or tenri@tci.org, or the curators Thalia Vrachopoulos at 646.344.9009 tvrachopoulos@gmail.com, or Suechung Koh at 201.724.7077 pariskoh@gmail.com Hyunjoo Park : The Light of Reason

Critic, Thalia Vrachopoulos

박현주의 작업의 핵심이 빛에 관한 것이라고 비평가들에 의해 알려져 있지만, 순수한 형태가 보는 이와 상호 작용한다는 점에서 포스트 미니멀리즘 미학의 관점에서도 논의 되어질 수 있다. 작가는 장소 특정적 작업을 통해 전시 공간을 작품 내부에 결합시킨다. 흰 벽에 설치된 육면체들은 그림자를 드리우며 이차적인 패턴을 형성하는데2015년 작 <Nirvana 3(각 13.8x6”)>의 경우 그림자가 견고하고 독자적인 요소로서 직육면체의 조각 작업에 더해짐을 볼 수 있다. 이러한 전경과 배경간의 모호함은 감각된 정보들을 전체로 조직화하려는, 또 주어진 조건 하에서 가장 단순한 쪽으로 인지 하기 위해 시각적 대상을 채워진 부분과 비워진 부분으로 분리하려는 인간의 성향을 설명해 주는 게슈탈트(Gestalt) 심리학의 관점으로 이해할 수 있다. 가장 단순한 기하학적 형태를 유지함으로써 작가는 채워진 것과 비어있는 것 간의 상호작용 뿐만 아니라 2차원 평면과 3차원 공간 사이의 상호작용에도 관여한다. 한편 박현주의 작업에서는 옵아트의 선구자 빅토르 바자렐리(Victor Vasarely)의 양식으로부터 전이된 듯한 파동을느낄 수 있다. 바자렐리는 60, 70년대에 선보인 작업들을 통하여 다음 세대 작가들이 움직임에 대한 시각적 실험과 2차원의 평면의 끝없는 가능성에 대한 실험을 이어나가는 동기를 제공하였다.

이러한 맥락의 연장선 상에서 박현주의 작업은 50년대 바자렐리의 작업처럼 기술적인 요소들도 포함하고 있는데, 스프레이로 페인트를 분사해 기계적 방식으로 직사각형혹은 원형의 형태를 구현해 내며 미묘한 색의 명암으로 광학적 현상을 연상시키는 식이다. 누구나 접근할 수 있는 미술을 추구하던 바자렐리는 새로운 기술들을 실험하였으며 미술이 이틀 안에 전 세계 어느 곳에서든 전시 될 수 있는 미래와 그에 따른 예술 작품의 독자적 권위, 아우라(aura)의 상실을 예견하였다. 박현주의 모듈식 작업들은기계화 시대의 생산과 복제에 대한 발터 벤야민의 논의를 연상시킨다. <기계 복제 시대의 예술 작품>에서 벤야민은 예술작품의 아우라와 관련하여 “원본성에 대한 신비주의가 제거될 때 비로소 모두가 예술을 즐길 수 있다”고 하였다. 이러한 경향성을 반영하는 뒤샹의 레디메이드(Duchamp’s readymades)는 예술의 무게중심을 오브제 자체로부터 작가의 아이디어로 옮기는 미증유의 결과를 가져왔는데 박현주 작가는 마치 뒤샹이 그러했던 것 처럼 보는 이로 하여금 전통적인 미술 제작에 있어서 가장 근본적인 가치로 여겨져 왔던 것들에 대해 질문을 던지게 만든다.

<Light and Monad>연작(2015)과 모듈성으로 설명될 수 있는 박현주의 작업들은 포스트 미니멀리즘의 흐름 위에 있다. 과정에 중점을 두고 미니멀리즘의 연장선에서 추상성과 기계적 특성을 다양하게 확장시키려는 장소 특정적 미술로서의 포스트 미니멀리즘이다. 한편 작가는 여기에 또다른 의미를 부여하는데, “불완전하고 애매모호한 모순으로 가득찬 삶이라는 과정안에서 무엇을 얻을 수 있을까 고민하면서, 빛을 쫓아가는 작업 이야말로, 나를 찾아가는 과정의 연장선위에 놓인 행위임을 깨닫게 된다” 라고 덧붙이고 있다. (Exhibition Director, Thalia Vrachopoulos,tvrachopoulos@gmail.com)

The Light of Reason

박현주는 국내에서는 드물게 템페라를 연구한 화가다. 템페라는 수성용매를 섞어 제작한 그림을 일컫는 것으로 점착제(粘着劑)가 들어있지 않은 그림물감을 사용하는 프레스코와 비교된다. 그는 일본으로 건너가 동경예술대학에 재학하면서 템페라 연구로 박사학위까지 땄다. 작품활동도 활발한 편이어서 국내외 화랑, 즉 오사카 카wm갤러리, 필라델피아 크리클로아트 갤러리,동경 고바야시갤러리, 독일 DNA갤러리, 선화랑, 인화랑, 금산갤러리 등에서 각각 개인전을 가졌다. 이번 빛갤러리 개인전은 작년 선화랑에서의 설치전에 연이은 국내전으로 평면작품과 일부 저부조 작품이 출품된다.

박현주의 작품에는 ‘금박’(Gold Leaf)이 빠지는 법이 없다. 옛부터 내려온 수법을 이어받아, 금박을 원하는 모양대로 잘라 지지체에 조심스럽게 붙이고 주위를 아크릴 물감으로 도포하거나 템페라로 덧칠을 해간다. 중세 제단화에서 천상의 빛, 신성과 그리스도의 영광 등을 나타낼 때 이용한 금박을 자신의 방법론으로 삼는 것은 작가가 사실의 전달보다는 초월적인 가치에 더 관심을 두고 있다는 표시로 읽힌다. 구체성이 희미해지는 대신 그 자리를 영원성과 불멸의 정신성으로 대체시킨다. 그 자신도 “물체인 오브제가 빛을 입는 순간 그 물성을 상실하고 전혀 다른 존재로 승화”한다고 적고 있다. 더 구체적으로 “2,3차원에 속했던 오브제가 다른 차원으로 ‘이행’하는 것으로써 물질로서의 오브제가 물질을 초월한 공간으로 옮겨간다.”(작가노트) 박현주의 스승인 사또 이찌로교수(동경예술대학)가 말하듯이 박현주는 “과거의 영원한 예술의 본질과 정신을 이어가고자 하는 마음가짐”을 느낄 수 있는데 이런 언급에서 그가 금박을 애용하는 이유를 대충 짐작할 수 있다.

박현주의 금박 작업은 ‘천사같은 사람’이란 뜻을 지닌 ‘프라 안젤리코’(Fra Angelico)의 을 모사하면서 시작되었다. 또 이탈리아 산마르코 수도원에서 안젤리코의 벽화를 돌아본 뒤 “천사나 성인의 얼굴엔 어디에선가 본 듯한 친근한 기원이 감돌았고, 붓질의 표현을 통해 프라 안젤리코가 참으로 따듯한 가슴을 지닌 사람”이었음을 느꼈다고 토로했다. 안젤리코의 작품에 매료되면서 작품생활을 하는데 큰 도움을 받은 셈이다. 단순히 재료적 흥미만이 아니라 도미니크교단의 수사였던 사제로서의 기독교적 정신세계도 크게 작용했을 것이다.

이번 작품전에는 대략 세가지 유형의 작품이 출품된다. 하나는 기하학적인 패턴으로 된 그림이요 둘째는 가족그림이요 셋째는 직육면체의 오브제 작업이다.

먼저 기하학적 패턴의 그림인 을 살펴보면, 바탕에 금박을 입히고 그 위에 형형색색의 동그라미가 그려져 있다. 삼각편대를 이루고 가장자리에 다시 동그라미가 에워싸고 있다. 중앙이 비어 있는 것같지만 가만히 들여다보면 그 안에도 실선의 동그라미가 들어 차 있다. 물론 조심스럽게 금박을 붙인 동그라미다. 둘째 가족그림인 에 있어서도 금박이 들어간다. 몇 년전에 작고하신 부친을 비롯하여 모친, 사랑스런 외동딸, 두명의 조카, 남동생 부부를 특수 제작한 원형의 캔버스에 새겨넣었다. 가족애를 다시 한번 확인하고 어머니로서, 이모로서, 딸로서, 언니로서 혈육의 정을 되새기는 심정이 들어있다. 게다가 오랜 유학으로 그간 부모님께 효도하지 못하고 딸에게 충분히 사랑을 나누어주지 못한 미안한 마음도 곁들여 있다. 셋째 오브제 작업은 직육면체의 구조물 상단을 칼라로 입히고 측면에는 금박을 입혀 금빛이 찬란한 원색과 더불어 반짝이게 만들었다.

금박의 사용과 함께 형식적으로 대립되는 두 요소의 병치도 눈에 띈다. 그의 작업은 상반된 요소들로 구성되어 있다. 평면과 입체, 원형과 사각, 빛과 색, 수직과 수평 등. 대수롭지 않은 것같지만 이러한 상반된 요소들은 우리 삶과 연관성을 지닌다. 즉 영혼과 육체, 삶과 죽음, 자연과 문명, 시간과 공간, 기쁨과 슬픔 등을 환기시키는 메타포로 기용하고 있다. 그것이 대립으로만 끝나지 않고 빛의 은총속에서 종합되고 화해되는 특성을 엿볼 수 있다.

‘반짝거림’은 두 요인에서 연유한다. 하나는 금박 자체에서 나오는 것이고 다른 하나는 조명을 받아내는 빛이다. 광원이든 빛을 더 환히 드러내는 쪽이든 모든 작품에 빛을 드리움으로써 실체를 구성하는 요인을 인식시키려고 한다. 단순한 추상이나 인물그림이 아니라 빛에 의해 조명된 존재들을 재인식하려는 의도가 풍겨난다. 그런 점에서 작가는 물질세계에 주의를 기울이는 사실주의자가 되기는 어려운 것같다.

그가 추구하는 것은 시간과 공간의 구애를 받지 않는 불변의 질서이거나 영원한 정신이다. “태양의 빛이 유형적인 것을 육안에 보이게 하듯이 천상의 조명은 영원한 진리를 정신에 보이게 한다.”(F. 코플스톤) 그것은 배운다고 해서 도달할 수 있는 게 아니라 우리 영혼에 조명됨으로써 가능하다. 조명의 빛을 만질 수도, 입증할 수도 없지만 참되고 확실한 것만큼은 부정하기 어렵다. “아무리 사람이 이성적이고 지적일지라도 스스로 조명되지 아니하고 영원한 진리를 분유함으로써 조명된다.”(성 아우구스티누스)

그의 작품에 드리운 금빛은 성좌처럼 떠 있지만 필자가 보기에는 축복의 팡파르요 은총의 별빛으로 다가온다. 지금 그의 그림에선 즐거운 향연과 축제의 연회가 한바탕 벌어지고 있다. 실제로 그의 작품에는 찬란한 별빛이 동동 떠 있는 작품이 등장하는데 마치 ‘춤추는 영혼’을 보는 것과 같은 인상을 풍긴다. 어둠을 뚫고 난관을 통과하고 아픔을 치유할 길은 ‘불멸의 빛’밖에는 다른 묘책이 없다.

박현주가 제시하는 빛은 희망이고 따듯한 온기요 생명의 펄럭임이다. 작가가 그런 경이로운 빛에서 눈을 뗀다는 것은 상상조차 하기 어렵다.

서성록(안동대 미술학과 교수)

박현주, 빛의 다이어그램

서성록(안동대 미술학과 교수)

Eunju Choi

Chief Curator

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea

Precisely a decade ago, in 2003, Hyunjoo Park published a book titled Inner Light. It was the repository of so many years’ assiduous work and researchthat she had conducted for her doctorate at Tokyo University of the Arts. In it is a preface written by the artist herself and I transcribe in the following a few sentences which I believe would move many a reader’s heart:

In creating a work of art, “life” presents to me the hardest, the most pressing problem. “Life,” which constitutes the theme of my studies and works, contains a tangle of so many binaries – living and dying, joy and sorrow, hope and despair – that you can’t really figure it out by dint of reason and knowledge. I wonder what we get out of such an incomplete and ambiguous grind that we call life …. Then finally I realized that by the work I do – that is, tracing light on canvas – I was actually in the process of finding myself.

Had Hyunjoo Park’s work at the time boasted the highest artistic caliber or possessed an authenticity that was just plain stupendous, then the above remarks would not have drawn as much attention. But we need to contemplate Park’s station in life that many years ago; she had at last completed herextensive and rigorous education to become a professional painter in various cities of the world from Seoul to New York to Tokyo and was finally, carefully and tremulously, testing the waters to enter the artistic career proper. If we could account that, then we might perhaps better grasp the depth of sincerity contained in her sentences that I excerpted above.

Fact is, not many people get to make a confessional statement like that. Even artists – that species touted to be the most self-immersed and -driven of all professional people – may not easily come across such an opportunity for self-reflection. In this age of overflowing tools and materials, artists may well be prepossessed by their chosen themes and subjects, materials and objects, be pushed and pulled by the pure momentum of their operations, then may at some point come face-to-face with demons that, try as you might, won’t easily be quelled. So the saying goes, the path of art is harsh, the life of artistsonerous. From very early on, Park has lived an honest life as an artist, by which I mean that she has tried to surmount the many negativities ineluctable in life – sorrow, despair, pain, what have you – and to heal her hurts by making art consistently themed around Light. Such efforts have now cohered intothis solo exhibition showcasing an ambient space of compositions, aptly titled <Temple of Light>.

You can say Hyunjoo Park hasn’t ever deviated from the theme of Light. But it should also be noted that over time – over a succession of distinctive periods each one characterized by a unique compositional style – her work has been gaining in depth and seriousness of engagement. <Sprouting> is a series produced in the earlier period of her studies in Japan, spanning about two years from 1998 to 1999. Park intended to tell a story about life-form by making consecutive circles in pencil on chalk ground. There she noticed with great interest and thrill the glittering particles embedded in the charcoal core of the pencil and this laid the foundation for her ensuing Light-themed works.

And then there is the Fra Angelico’s Linaiuoli altarpiece (1433-35) which Park seldom fails to mention in her biography as another crucial source of influence that compelled her to pursue the theme of Light. Meticulously reproducing the painting, Park was able to master the techniques of tempera and gilding, and this refined her eye for the expression of sacred Light as antithetical to secularity, ultimately giving rise to her most representative work to date, the <Inner Light> series, produced over a decade-period from 1997 to 2007. In this series, she most often fashioned cubes and boxes with wood panels, coated them in acrylic paint and gold leaf, then put them in vertical and horizontal arrangements, thus creating a strongly geometrical order. In this manner, Park maximally brought out the physical properties of light, that is, its absorption and reflection.

Subsequent works continued to reprise the theme of Light: <Beyond the Light> begun in 2008 features cylinders and cuboids rendered in riotously vivid colors; <Diagram of Light>, from 2009 onwards, arranged colored dots and bars in various rhythmic ways; <Floating of Light>, launched in 2010 and continuing, attempted to create wave-like impressions on canvas by expressing light and color in varying degrees of contrast and harmony.

In this exhibition, Hyunjoo Park seems to have gained more confidence in her art-making. This batch of works still speaks basically the same language as her past creations in which she experimented with various manners of visual composition, but it also exhibits quite a bit more verve and bravura; points, lines and planes rub shoulders in a single frame, or else these elements altogether fuse and create a wholly new kind of space. Also noteworthy is Park’s deft use of compound colors such as purple and turquoise, never before seen on her canvas, which further adds to her latest work’s flavor and nuance.

The gilded polka dots small and big – a staple feature of Park’s compositions – can be found in numerous configurations: some are huddled together like a friendly crowd; some stand apart like sullen loners; some seem to be in the middle of power struggle, taut and charged, ready to vault at any moment; some remind of a hand gesture signifying peace and reconciliation. In some cases, the dots are gathered inside a silhouette of what looks to be anhourglass, symbolizing finiteness of time. In some others, as they meet with a medley of lines – vertical, horizontal, oblique – the dots seem humanized, seem to be enacting interpersonal relationships. As such, these dots resemble nothing so much as human beings in all their complexities both glorious and damning.

As her compositions unfold, we start to discern certain recurring shapes; one by one pillars go up, stairs descend, roofs perch atop, revealing architectural forms reminiscent of the Tower of Babel, or some sacred halls of the pagan antiquities, or Buddhist temples perhaps. In any case, it is the kind of place that distills life-battered man’s deepest, dearest wishes and longings, reeled up from the very bottom of the human heart.

Named <Temple of Light> in dedication to her recently deceased mother, Hyunjoo Park’s solo exhibition contemplates her life as an artist and the values that have attended to and fermented with it. Living and dying, hope and despair, suffering and healing, lack and completion, light and shadow, secularityand sanctity, space and time….all these and more are dissolved in this temple; it is a place for all human souls.

The Temple of Light: A Place for All Human Souls

Eunju Choi

Chief Curator/Daegu Art Museum

정확하게 10년 전인 2003년, 박현주는 동경예술대학대학원에서 박사학위를 받은 것을 계기로 본인의 수 년 간에 걸친 작업과 연구 성과를 담은 <Inner Light>라는 책을 발간했다. 작가가 직접 쓴 그 책의 서문에 짧지만 읽는 이들을 감동시키는 몇 문장이 있어 다음에 옮겨 적는다.

“작품을 제작하는 과정에서 ‘삶’은 내게 가장 절실한 문제로 다가 오고 있다.

작품과 논고의 테마를 이루는 ‘삶’ 속엔 생(生)과 사(死), 기쁨과 슬픔, 희망과

절망 등의 상반되는 것들이 혼재되어 있어 우리의 이성과 지식으로는 명쾌한

답을 내릴 수 없다. 이렇듯 불완전하고 불명료한 삶을 통하여 우리는 무엇을

얻을 수 있을까. (중략) 그리고 마침내 화면 속에서 빛을 좇아가는 작업이

결국은 나 자신을 찾아가는 과정임을 깨닫게 되었다.”

이 시기 박현주의 작업이 아주 높은 예술적 수준이나 다른 작가들과 비교되는 확연한 참신성을 지니고 있었다면 위의 언급에 주목할 필요가 없었을 것이다. 그러나 서울, 뉴욕, 동경을 거치면서 긴 시간 화가가 되기 위한 공부를 마치고 이제 막 예술가로서의 행보를 조심스럽게 내딛기 시작했던 당시 박현주의 모습을 상기해 본다면 그 진정성의 정도가 어떤 것이었던가를 가늠케 한다. 사실 위와 같은 자기 고백의 기회를 많은 사람들이 갖게 되는 것은 아니다. 심지어 가장 자기중심적인 직업인이라고 할 수 있는 예술가들에게 조차 이러한 자기성찰의 기회는 의외로 쉽게 다가오지 않을 수 있다. 각종 재료와 물질이 난무하는 시대, 작가들은 자신들이 선택한 주제와 소재, 물질과 사물에 사로잡혀 작업의 관성대로 끌려 다니다가 어느 순간 자신도 어찌할 수 없는 괴물과 맞닥뜨리게 될 지도 모른다. 그래서 예술의 길, 예술가의 삶은 어렵다. 박현주는 일찌감치 신산한 삶이 가져다주는 슬픔, 절망, 고통 등 여러 부정적 요소들을 ‘빛’이라는 일관된 주제로써 스스로를 치유하고 극복해 나가는 작가로서의 솔직한 삶을 살아 왔다. 이런 작가의 노력은 이제 <빛의 신전(Temple of Light)>이라 명명된 조형적 공간 속에서 특별한 아우라를 발하는 국면을 맞이하고 있다.

박현주의 작업은 ‘빛’의 주제라는 큰 윤곽을 줄곧 유지해 왔지만 시기별로 각기 다른 조형성을 실험하면서 점점 더 해당 주제를 심화시켜 왔다고 볼 수 있다. <Sprouting>은 일본 유학 초기인 1998년과 1999년 약 2년간 시도되었던 연작이다. 백아지 위에 연필을 사용하여 동그라미를 연이어 그려나간 드로잉적인 그림을 통해 작가는 생명체에 관한 이야기를 하고자 했다. 그러나 우연한 기회에 연필의 흑연이라는 물질이 갖고 있는 광물 입자의 광택을 인지하게 되었고 이에 대한 흥미는 곧 ‘빛’의 주제를 자신의 작업으로 연결시킬 수 있는 자양분이 되었다. 물론 이 즈음에, 이 작가의 화력에서 항상 언급되는 프라 안젤리코(Fra Angelico)의 <리나월리(Linaiuoli)성모자상>(1433-35) 모사 수업도 ‘빛’에 관한 작가의 관심을 천착하는 계기가 되었다. 성상화를 모사하는 작업을 통해 작가는 템페라와 금박 기법을 아주 충실히 습득하게 되었고 이를 통해 세속성에 반하는 신성한 ‘빛’의 표현에 눈뜨게 되었다. 이렇게 해서 탄생한 <Inner Light>는 1997년부터 2007년까지 무려 10년간이나 지속되면서 박현주의 가장 대표적 연작이 되었다. 나무 패널로 제작된 직육면체나 정육면체의 표면을 물감과 금박을 사용해 도포하고 이를 수평과 수직의 기하학적 질서 속에 놓이게 하는 방식이 주로 채택되었다. 이렇게 함으로써 작가는 빛의 흡수와 반사라는 물리적 성질을 극대화하였다. 2000년대 후반기에 작가는 <Beyond the Light> 연작(2008년~)에서 비비드한 색상을 원형과 직육면체의 구조물에 경쾌하게 얹어 본다든지, <Diagram of Light> 연작(2009년~)에서 컬러 도트(Dot)나 바(Bar)의 리드미컬한 배치를 시도해 본다든지, <Floting of Light>연작(2010년~)에서 색과 빛의 대비와 조화를 통해 공간에 파장을 일으키는 등의 시도를 해왔다.

이번 전시에서 작가는 과거의 다양한 조형적 실험을 기반으로 이제 자신이 보다 과감한 화면 구성을 할 수 있음을 자신감 있게 보여주고자 한 듯하다. 점, 선, 면이 하나의 화면 속에서 종합되거나 이 조형적 요소들이 결합하여 새로운 공간이 연출되고 있다. 또한 작가는 이전에 사용한 바 없는 자주색과 청록색 같은 혼합색을 능란하게 사용하여 작품의 독특한 분위기를 배가시키고 있다.

화면 속에 어김없이 등장하는 금박으로 처리된 크고 작은 원형의 점들은 마치 인간 존재를 상징하는 것처럼 다정히 모여 있기도 하고, 홀로 떨어져 고독하기도 하고, 때로는 힘겨루기를 하는 듯 팽팽히 맞서기도 하고, 다른 경우에는 손 내밀어 화해하는 듯한 제스처를 취하면서 공간을 탐색한다. 어떤 경우에는 이 점들이 모래시계를 연상시키는 실루엣 속에 놓여 시간의 유한함을 상징하는 것도 같고 수평선과 수직선, 사선과 만나다보니 인간과 인간사이의 관계를 암시하는 것 같기도 하다.

그러다보니 어느새 이 작가의 화면에 하나 둘 기둥이 생기고 계단이 만들어지고 지붕이 얹어지면서 고대 그리스 로마의 신전이나 바벨탑, 혹은 불교사원일 수도 있는 건축적 형상들이 슬며시 드러나고 있다. 삶의 절실함을 체험한 인간의 염원이 반영된 신전의 형상이 이 작가의 작품 속에 자리 잡게 된 것이다. 얼마 전 작고하신 어머니에게 바치는 헌정의 뜻을 담아 <빛의 신전(Temple of Light)>라 명명한 이번 개인전을 통해 작가는 예술가로서의 삶과 그 삶에 동반되는 가치를 되새기고 있다. 그래서 이 신전은 삶과 죽음, 절망과 희망, 고통과 치유, 완성과 미완성, 빛과 그림자, 성(聖)과 속(俗), 시간과 공간을 존재하게 하는 모든 영혼의 집이다.

빛의 신전, 영혼의 집

최은주(대구미술관 관장)

When we think of Park Hyun-joo, we are reminded of gilt wooded cuboid bars that give off a golden gleam, geometric compositions of horizontal and vertical lines, and an optical illusion by lively long bars and dots in pastel tones, under the theme, ‘Light’, which she has long explored. She has repeatedly used simple formative elements such as parallel lines and circles, and stirred up a vibration or an optical illusion through the combination and arrangement of multiple colors. In terms of visual effect, her works are similar with those in optical art. But if you deeply look into them, you can see that she does not confine her art to a specific style but has developed her own world with different forms and stories.

Park Hyun-joo’s works are divided into two-dimensional works on the canvas and three-dimensional works on the wall. For this exhibition “Light - Monad” she has installed three-dimensional works made with wooden cuboids. The works in the exhibition have been more simplified than her previous pieces for which she attempted diverse formative experiments: the bars painted in the canvas have been evolved into three-dimensional units. In particular, she has given a gradation effect to the surfaces of wooden cuboids with a sponge roller, and expanded her color spectrum from a monochromatic to a polychromatic tone, as if the light passing through a prism is separated into multiple colors and covers a three-dimensional surface. If a line causes a visual effect of optical art, color causes a visual effect of Park Hyun-joo’s art.

Along with color, what maximizes the visual effect of Park Hyun-joo’s work is splendid gilt. Park Hyun-joo has been using the gilt technique, a core of her work, since she was first attracted to the technique in the reproduction of the Italian Renaissance painter Fra Angelico’s “Madonna and Child (Linaiuoli)” during reproduction practice at a research center for oil painting materials while she was studying at Tokyo University of the Arts. The gilt technique, which she encountered by chance, has led her to her current style. The holy light of tempera in gold color became a chance that has allowed her to contemplate the preposition of light.

Park Hyun-joo’s gilt is a mirror that reflects her life’s attitude: “I want to show that contrasting elements, such as reality and unreality, material and spirit, two dimensions and three dimensions, verticality and horizontality, and squares and circles, can be harmonized on a canvas.” In the context of the German philosopher, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who stated that a monad with no window is a mirror of the living universe that makes every body and mind harmonized [1], the gilt of Park Hyun-joo, which has the characteristic of reflecting objects, acts as a mirror. Another characteristic of gilt is visual illusion. She did not apply gilt onto the fronts of her works but to their sides, so that they give off a secretive and mysterious feeling, stirring up a regular reflection, as if they are shining on their own. In addition, her gilt causes an illusion as if the pieces are two-dimensional owing to the reflection effect in which the lights of the pieces collide with each other. In this way, the gilt planes of her works are special as a formative element that features her unique world, along with the visual effect of the color. It is clearly different from the light art that reveals the effect of light by maximizing its display through scientific tools and technology.

Along with her expression method, what we must pay attention to in this exhibition is the title, “Light – Monad.” She has accessed the term, monad, in terms of its definition: a ‘monad is ‘an unextended, indivisible, and indestructible entity that is the basic or ultimate constituent of the universe and a microcosm of it, and is a principle of the life activity of the universe that expresses the whole ideas of the universe.’ The unit that she used for her objects shares many things in common with the monadology of Leibniz in which he formed a type of metaphysics by taking the ‘monad’ as the ultimate principle unit of the universe. As Leibniz explained through the composition of a monad in a metaphysical structure (a part and a whole), Park Hyun-joo has accessed the unit of light with such a metaphysics. Like the monadology of Leibniz, which emphasizes the transfer of perception that returns to the starting point again after moving from the small (microcosm) to the large (macrocosm) and from the part (one) to the whole (many things), her units are individual, and at the same time become a whole painting, relating to each other organically. This is related with the view that ‘one is a whole and a whole is one.’

Park Hyun-joo has adopted the ‘monad’ as the key word of this exhibition, but the world that she actually tried to express through ‘Light – Monad’ is light as a type of self-discipline and healing, like in her older work. She has paid attention to the spiritual and symbolic aspect of light beyond its physical characteristics such as wavelength, adsorption, and reflection. In short, she has laid emphasis on an inner realization rather than external splendor, thinking of the process of exploring light as the process of exploring herself. It can be related with her view of the world that has been held since she created the series “Inner Light” over a ten-year period (1997 – 2007). In her art note, she wrote, ‘I want to describe the world where contrasting elements can go together and the world can console tired souls and relieve their burden in today’s unclear and dark reality.’ She does not divide the East and the West in her world. Although her gilt technique was borrowed from holy images of Christianity in the Renaissance, the world she pursues is closer to Eastern spirits. This is revealed in Buddhist terms and topics that she used. Like the Buddhist term ‘gonggwan’ in Korean, commented upon in the documentation “Inner Light,” a term that means ‘meditation on voidness’ (this is a method of meditation by which one realizes the law that all elements in the world are non-substantial and empty), in this exhibition as well, she has disclosed her view of the world with the Buddhist term ‘Nirvana,’ a term meaning a beatitude that transcends the cycle of reincarnation characterized by the extinction of desire and suffering and individual consciousness. After all, to Park Hyun-joo, light is a hope that transcends the religions of the East and the West and is the energy of her life.

Light is transcendental. We cannot confine it in a specific space and fix it as a specific image. As there is no absolute space or absolute time, there is no absolute light. As the monadology of Leibniz is a philosophy that surpasses the five senses and scientific systems, light cannot be defined as a single form or explanation. It only works as a power that allows us to be aware of beings in the time and space where we are. It is impossible to try to keep light in our time from the beginning. In this point, if the way in which she has held her exhibitions thus far is a limited attempt that uses light artificially, it is expected that she will try to make the inner side of her works meet with the characteristic of light more naturally. In addition, her future work needs a more elaborate logic that can cover the key words of Leibniz’s monadology (monad, god, and the world) and her world of light at the same time.

Ultimately, the illusion of light of Park Hyun-joo’s works is an expression of her faith in the world that she cannot feel with the senses of sight and touch. And it is a projection of eternity for which she has drawn monads, the true atoms of nature, into her own light world, “Light – Monad.” The exhibition “Light – Monad” is an aura of light that is revealed by the delicate perception of the artist Park Hyun-joo, who is always trying to change herself like a light that is reluctant to dwell in a particular place.

Park Hyun-joo’s Light - Monad, The Eternal World

Byeon Jong-pil (director of Yangju City Chang Ucchin Museum of Art, art critic)

박현주 작가하면, ‘빛’이라는 주제 하에 화려한 금빛을 발산하는 육면체의 금박나무패널박스, 수평과 수직의 기하학적 화면구성, 생기 있는 파스텔톤의 긴 바(Bar)와 점(Dot)이 이뤄내는 착시 효과 등을 선보이는 작업이 떠오른다. 평행선, 동심원과 같은 단순 조형요소를 반복적으로 사용하고, 색채의 다중 조합과 배치를 통한 진동이나 동요를 일으키는 시각적 착시를 유발하는 작업을 통해 ‘빛’에 대한 탐구를 지속해왔다. 시각적 효과라는 측면에서는 옵티컬아트와 맥락적 유사함을 지녔지만, 주의 깊게 들여다보면 작가가 추구해온 일관된 작품세계가 단순히 특정 미술사조에 국한되지 않은 차별화된 형식과 내용으로 자신만의 작품세계를 이끌고 있음을 확인할 수 있다.

박현주의 작업은 크게 캔버스를 이용하는 평면작업과 반 입체의 성격을 띠는 입체작업으로 양분되는데 이번 <빛의 모나드>전시는 각각의 유니트(unit)들이 모여 무리를 이루는 식의 공간 설치 방식을 채택한 입체작업이 주를 이룬다. 과거 다양한 조형적 실험을 시도했던 화면구성에서 한층 간결하고 단순해진 표현형식을 취하였다. 기존의 평면화면 속 바(Bar)와 점(Dot)이 독립적 개체로 분화되어 입체화한 형식이다. 특히 개별화된 유니트 표면을 스폰지 로울러를 이용하여 그라데이션 효과를 극대화하고, 단색조에서 다색조에 이르는 색의 스펙트럼을 넓힌 것이 눈에 띈다. 마치 프리즘을 통과한 빛이 다양한 색조로 분사되어 입체표면을 덮고 있는 듯한 느낌을 준다. 옵티컬 아트의 시각적 효과를 이끈 것이 선(線)이었다면, 박현주 회화의 시각적 효과를 리드하는 것은 색(色)이다. 박현주 회화에서 만날 수 있는 독자성이다.

색과 더불어 박현주 입체작업의 시각효과를 신비롭게 만드는 것은 화려한 금박이다. 그녀 작업의 핵심으로 알려진 금박기법은 동경예술대학 재학 중 유화재료기법연구소에서 해마다 실시하는 모사실습수업과정에서 프라 안젤리코의「리나월리(Linaiuoli)성모자상」을 모사할 당시 그 그림에 사용된 조형기법에 매료된 이후 사용해온 기법이다. 재현을 통해 표현방법을 탐구하던 중 우연히 마주하게 된 금박기법이 현재의 작품세계를 이끌었다. 한마디로 황금배경 템페라의 성스러운 빛이 ‘빛’이라는 근원적인 명제에 이르게 된 계기였다.

“성상화는 내가 이제껏 경험하지 못한 새로운 시각 경험 중 하나였다. 그것을 처음 보았을 때 마치 그림 속에서 빛이 나오는 듯한 느낌을 받았다. 템페라 물감의 선명한 색채와 눈부신 금박은 서로 강하게 대비되면서도 훌륭한 균형을 이루고 있었다.”「Inner Light」Documentation, 2003 중에서)

박현주의 금박면은 ‘현실과 비현실, 물질과 정신, 입체와 평면, 수직과 수평, 사각과 원 등의 서로 모순되면서 대조되는 요소들이 한 화면 안에서 어우러질 수 있는 세계임을 보여주고 싶다’라는 그녀의 삶의 태도를 비추는 거울이다. 작품에서 금박면은 정면이 아닌 측면에 표현되어 벽면에 설치된 다수의 오브제가 측면끼리 정반사를 일으키며 자체적으로 빛을 발산하는 듯한 신비로움을 준다. 또한, 오브제가 서로 부딪히는 반사효과로 평면 같은 착각을 일으킨다. 이처럼 금박면은 색의 시각적 효과와 더불어 그녀의 작품세계를 특징짓는 조형요소로 각별하다.

박현주의 전시에서 표현기법의 개별성과 더불어 주목 할 것은 ‘빛의 모나드’라는 전시 타이틀이다. 박현주는 지금까지 16번의 개인전을 열었는데, 그동안 전시의 타이틀로 ‘빛’을 직접적 드러낸 것은 2008년부터이다. ‘beyond of Light’(2008), ‘diagram of Light’(2009), ‘floating Light’(2011), ‘빛의 성전’(2013), ‘빛을 쌓다’(2014)까지 이어진 전시명에서도 빛을 탐구해온 작가의 여정을 읽을 수 있다. ‘beyond of Light’, ‘diagram of Light’, ‘floating Light’ 까지는 빛이 지닌 파장, 흡수, 반사 등 빛의 물리적 특성 등에 초점이 맞추어져 있었다면, ‘빛의 성전’과 ‘빛을 쌓다’에서는 빛의 성질보다 궁극에 빛으로 이뤄내고 싶은 성과(결과물)에 무게를 두었다. 이는 10년(1997~2007)간 지속했던 연작「Inner Light」에서부터 축적해온 세상을 바라보는 시각인 삶의 자세와 연관 있다. 빛을 좇아가는 과정을 자신을 찾아가는 과정으로 여기며 외형적 화려함보다 내면의 깨달음을 중시했다. 성스러운 빛을 발산하는 성전처럼 물리적 특성이 아닌 정신적 깨달음을 주는 빛의 표현에 몰입했다. <빛의 모나드>전의 작품들도 비슷한 연장선에 있다.

작가는 모나드(monad, 單子) 의 사전적 정의인 ‘무엇으로도 나눌 수 없는 궁극적 실체로, 비물질적이며 우주의 일체의 사상을 표출하는 우주의 생명 활동의 원리’의 측면에서 접근했다. 작업에서 반복되는 오브제의 유니트가 ‘단자를 궁극의 원리로 하여 형이상학을 구성’하는 라이프니츠의 모나드론과 상통한다는 개념으로 보고 있다. “유니트들은 개별적이면서 동시에 전체 그림의 한 조각을 이루며 서로 유기적으로 연결되어 있다. 본질을 추구하는 나의 작품 성향은 우리의 감각과 사유가 미치지 못하는 곳을 그리워한다. 각각의 모나드로 고독에 처한 우리는 벽을 허물고 하나가 되는 전체를 꿈꾼다.”고 적은 작업단상은 라이프니츠가 모나드론에서 작은 것(소우주)에서 큰 것(대우주)으로, 단순(하나)에서 복잡(여럿)으로 이동한 후 다시 복잡에서 단순으로, 큰 것에서 작은 것으로 회귀하는 지각 이동을 강조한 부분과 일맥 상통한다. 단순실체인 모나드는 각자의 관점에서 우주를 본다. 때문에 각자의 관점만큼 다양성이 생기고, 그에 따른 질서가 마련된다. 박현주의 ‘빛의 모나드’는 라이프니츠 모나드론의 근본정신에서 출발하고 있다. 라이프니츠가 모나드의 구성원칙을 부분과 전체라는 형이상학적 구도로 설명한 것처럼 박현주는 빛의 단위를 근본적인 형이상학으로 접근했다.

박현주는 누구보다 자신의 창작과정을 철학적으로 사고하고 접근하는 것을 습관화한 작가이다. 이는 자신의 삶과 예술을 그림이 아닌 언어로 솔직히 토로한 작업의 단상에서 어렵지 않게 발견할 수 있다.

‘내가 꿈꾸는 빛의 세계는 물질과 비물질(정신, 영혼)의 경계 위에서 마치 공기 중을 부유하는 나비가 바라보는 세계와 닮아 있다. 우리는 어디에서부터 와서 어디로 가고 있는가. 어찌 보면 우리의 삶 자체가 미지의 세계를 쫓아가는 ‘빛의 시각적 환영’ 속에 있는 것인지 모른다’는 글이나 ‘작업이 삶의 에너지와 위로를 주고 생명의 빛으로 향하는 길을 인도하는 삶을 사랑하는 이유인지 모르겠다’라는 고백은 솔직한 자기고민의 흔적이다.

철학적 사고의 깊이만큼 창작과정이 온전히 성과로 이어지는 것은 작가의 몫이다. 이 점에서 박현주가 그린 빛의 세계가 라이프니츠의 <모나드론>의 핵심주제인 ‘모나드, 신, 세계’와 어떻게 연결되는가는 그녀의 예술적 가치와 의미를 해석하는 또 하나의 기준이 될 것이다.

박현주는 ‘모나드’를 이번 전시의 핵심어로 삼았지만, 실질적으로 <빛의 모나드>를 통해 표현하려는 세계는 기존 작업과정과 마찬가지로 자아성찰을 위한 자기수행과 치유로써의 빛이다. “서로 모순되면서 대조되는 요소들이 한 화면에서 어우러질 수 있는 그런 세계, 불확실하고 어두운 오늘날의 현실에서 삶에 지친 영혼의 무게를 조금이나마 덜 수 있고 위로 받을 수 있는 그런 세계를 그리고 싶다.(작가노트)”는 고백의 실천이다. 여기에는 동서양의 구분도 없다. 금박기법은 성상화에서 차용했지만, 정작 추구하는 작품세계는 동양적 정신세계에 밀착되어 있다. 이는 불교적 세계관을 지닌 용어나 화제에서 드러난다.「Inner Light」Documentation 에서 언급했던 ‘공관(空觀, 현상의 배후에 고정적인 실체는 없다)’처럼 이번 전시에서도 ‘니르바나’(Nirvana, 涅槃, 일체의 번뇌를 해탈한 불교의 최고의 높은 경지) 라는 범어를 화제로 삼은 부분에 지향하는 세계관을 드러냈다. 그녀에게 빛은 동서양의 종교를 초월한 희망이며, 살아갈 수 있는 생의 에너지이다.

빛은 초월적이다. 특정 공간에 가둘 수 없고, 특정 이미지로 고정할 수 없다. 절대공간이나 절대시간이 존재하지 않은 것처럼 절대 빛은 없다. 라이프니츠의 모나드체계가 오감과 과학체계의 모든 것을 뛰어넘는 철학정신이었듯이 빛은 하나의 형식과 내용으로 규정짓거나 가둘 수 없다. 단지 머무는 시간과 공간에 따라 실체와 존재를 지각하게 하는 힘으로 작용할 뿐이다. 빛을 인간의 시각 속에 잡아두겠다는 시도는 애초에 불가능하다. 이 점에서 박현주의 이제까지 작품이 빛을 인공적으로 연출하는 제한적 시도였다면, 이제는 작품의 내면과 자연이 발산하는 빛의 특성이 한층 자연스럽게 만나 빛의 숭고한 느낌이 발산되도록 연출하는 방법도 시도할만하다.

궁극에 박현주의 작품이 뿜어내는 빛의 일루젼은 시각과 촉각으로 확인할 수 없는 미지의 세계에 대한 신념의 표현이다. 자연의 참된 원자인 모나드를 ‘빛의 모나드’라는 자신만의 빛의 세계로 이끌어낸 영원(永遠)의 투영이다. <빛의 모나드>전은 한 곳에 머물지 않는 빛처럼 언제나 자기변신을 꾀하는 박현주 작가의 섬세한 지각이 발현하는 또 다른 빛의 아우라를 만날 수 있는 기회이다.

박현주의 '빛의 모나드', 그 영원의 세계

변종필(미술평론가)

스승과 제자로써 박현주와 인연을 맺은 지 벌써 5년째로 접어들고 있다. 나는 박현주의 작업 활동을 옆에서 지켜 보고 온 한사람으로써 내가 바라본 박현주에 관하여 몇가지 이야기 하고자 한다. 현재 박현주는 동경예술대학 미술학부 대학원 석사과정을 거쳐 박사과정1년차에 재학중이다. 일본에서는 Gallery Q(1997년), 고바야시 화랑(1998년)에서 개인전을 가졌으며, 그 이외 다수의 단체전에도 적극 참가해 왔으며, 금년11월에는 현대미술의 유망주의 한 사람으로써「ART-ING TOKYO 1999;21☓21 presented by SAISON ART PROGRAM」에 선정되어 개인전을 가진 바 있다.

박현주는 서울대학교 미술대학 서양화과를 졸업 한 후, 뉴욕 대학 회화과에 유학하였는데 당시의 회화 작품은 모더니즘이 발견한 순수한 유희 충동에서 보여 지는 듯한, 그리는 행위의 원초적 충동과 같은 아름다움이 화면 가득히 배여져 있는 미국의 전후 추상 표현주의 양식에 영향 받은 듯한 작품들이 대부분이었다. 그리고 잠시 한국에 머무는 동안 박현주는 작품의 변화를 맞이하게 되었다. 당시 내가 본 박현주의 작업은, 흘러내리는 듯한 유연한 붓의 운동감이 화면에서 사라지고 恨의 감정이 작품의 밑바탕에 깔려있는 듯한 다소 경직된 화면이 인상적이었다. 그러한 시기에 나는 박현주 학생의 지도 교관으로써 동경에서 만나게 되었고 나로서는 그녀가 내부에 잠재된 응어리를 화면 안에서 풀 수 있게 되기를 바라면서 일본이라는 새로운 환경 속에서 나오는 새로운 작품을 기대하게 되었다. 그 후1997년도 일본에서의 가진 첫 개인전에서, 박현주의 작업은 또다시 변화를 맞이한 듯 했다. 이전 작품에서 보여진 눈물과 같은 딱딱한 형태는 화폭 속으로 녹아 들어가게 되었고, 세포와 같은 형태는 생명체를 암시하기도 하는 듯이 원초적인 형태로 다시 표출되면서 화면 위를 부유하게 되었다. 그러나 뉴욕에서의 작품에서 보여준 색채의 범람은 사라졌고, 단색계의 차분한 색조가 화면을 뒤덮고 있었다.

이러한 시기에 박현주는 우에노 캠퍼스에서 1시간이상 떨어진 토리떼 캠퍼스로 통학하면서 학부생 대상의 「회화기법사 재료론」을 수강하였다. 강의 내용은 서양화, 동양화를 포함한 회화의 원리를 재료와 기법적인 측면에서 고찰해보자는 것이었다. 나는 회화를 형성하는 데 있어서 표현과 기법이라는 두 가지 요소가 결코 분리될 수 없는 관계에 있다는 사실을 매번의 강의를 통해 강조했던 기억이 난다. 당시 우에노 캠퍼스에서는 사토-기지마 세미나가 주 1회 진행되고 있었는데 세미나의 내용은 Daniel V.Thompson의 『템페라화』의 영문 번역과 병행하여 13세기 초기 이태리 르네상스 시기의 황금배경의 템페라화를 모사하는 것이었다. 모사 수업은 작품의 지지체(support)에서부터 시작하여 밑바탕칠(ground), 부조(pastiglia), 금박 입히기(gilding), 각인(punching), 채색에 이르기까지 되도록이면 당시의 탬패라화를 그대로 재현하는 방향으로 이루어졌다. 박현주는 Fra Angelico의 성모자상(1433-5년작)을 부분 모사하였는데, 시대가 바뀌어도 변하지 않는 모자간의 모습이 아주 진솔하게 표현되었던 것으로 기억된다. 유화기법 재료연구실의 또 하나의 수업인 사까모토- 다키나미의 세미나인 크리틱에서는 사진과 텍스트를 이용하여 자신의 작품을 프리젠테이션하는 것이었다. 박현주는 세미나에 적극적이고 성실한 자세로 참여하였는데 이러한 수업의 성과들이 그녀의 작품에 여실히 드러나고 있다고 여겨진다.

성상화라고도 일컬어지는 초기 이태리 르네상스시기의 템페라화는 배경이 금박으로 처리되어 있다. 금박으로 처리된 배경 부분은 숙련된 수 작업으로 연마된 탓으로 흡사 거울면과도 같은데 여기에 빛이 닿으면 빛은 굴절,흡수 되지 않고 거의 정반사를 일으킨다. 따라서 반사광에 의한 빛의 효과는 마치 금박면 그 자체가 빛을 내고 있는 것처럼 보이게 된다. 여기서 빛을 발하는 금박면은 성인의 후광 또는 광배를 의미하며, 그것은 바로 성스러운 빛을 제시한다. 미술사가 곰브리치는 이를 가리켜 빛의 즉물적 도입이라고 표현하고 이 후 르네상스를 거쳐 바로크시대로 이어지는 회화의 특징과는 다른 선상에 놓인다고 보았다. 즉, 회화의 양감과 공간처리에 있어서 금박면은 점차 사라지고, 백색 물감에 의한 명암 단계의 표현이 화가 스스로에 의해 구축되기 시작하였다. 이것은 르네상스와 바로크로 이어져 내려오는 회화의 기법상의 특징이기도 하다.

여기서 박현주는 황금배경 템페라화의 「성스러운 빛」에 주목하고 있다. 그러나 금박면은 정면이 아니라 측면으로 이동되면서 측면의 깊이에 두께를 증폭시키게 된다. 따라서, 회화라기보다는 오브제에 가까운 형태로 변하게 되면서, 오브제는 단일 갯수가 아닌 복수로 제시되고 있다. 벽면에 설치되어 있는 오브제들은 빛이 닿으면서 측면끼리 정반사를 일으키는데 이로 인해 시각적으로 측면이라는 실체는 사라지게 된다. 결과적으로 우리는 빛 그 자체가 서로 반사되는 현상만을 감지하게 된다. 한편 정면은 각각의 면적이 측면에 비해서 축소됨과 동시에 백색화 된다. 그 백색은 실체가 사라진 공간에 질서 정연하게 집합체로 구성되고, 나아가서 백색 오브제의 집합체로 인한 일종의 환영(illusion)이 생성되어, 마치 오브제들이 흰 벽면 위를 부유하고 있는 듯 한 착각을 불러일으킨다. 이것은 박현주의 내면에 깔려있는 내재된 잠재의식의 표출이라 보여 지며, 또한 20세기 예술을 특징 짓는 단어이기도 한, 순수화, 구성화, 무의식화, 절대화라는 모더니즘의 코드로 읽혀질 수 있을 것이다. 그러나, 21세기를 바로 눈앞에 두고, 기도하는 감정을 삶으로 하는, 즉 과거의 영원한 예술의 본질과 정신을 이어나가고자 하는 마음가짐이 박현주 에게서 느껴진다. 그리고 거기에서 탄생되는 작품들을 나는 앞으로 계속 지켜볼 것이다.

박현주의 1999년 개인전 서문에 부쳐………

동경예술대학 미술대학 교수 사토 이찌로

본인의 작업은 눈에 보이지 않는 빛의 세계를 물질로써 재현하여 빛의 시각적 환영을 만들어내는 일이다.

한 해 한 해 살아가면서 느끼고 생각하는 일들을 “빛”이라는 주제를 통해 근 몇 년간 작업해오고 있다. 전시라는 형태를 빌어 작품을 통하여 세상과 소통 한다는 일은 매우 매력적인 일이다. 특히 세상과의 소통이 원활하지 못한 나같은 성격으로는 그리 나쁘지만은 않은 직업이라는 생각도 든다. 작업이라는 일이 마치 정해놓지 않은 목적지 없는 여행을 떠나는 것과도 같아서 작업 과정에서 일어나는 예기치 않은 일들로 뒤범벅이 되는 경우도 많고 반면 생각지도 못하는 일들로 인해 예상 외의 희열을 얻기도 한다.

그러나, 내가 지향하는 빛의 세계가 어떤 것인가에 대한 해답은 아직까지도 그리고 여전히 혼란스러운 것이 사실이다. 작업을 하는 과정은 어찌 보면 빛을 따라가는 일과도 너무나 많이 닮아 있어서 빛을 화두로 하는 본인의 작업은 앞으로도 긴 여정의 시간이 필요할 것 같다.

작업내용에 대해 좀 더 이야기한다면, 나는 ‘빛을 그린다’는 의미에서보다 어떻게 하면 ‘빛을 재현해낼 수 있을까’에 더 많은 관심을 두고 있다. 빛에 관한 재현의 문제를 회화라는 이차원의 평면 안에서 풀어나가려는 의지는 아마도 나의 의식과 무의식의 전반에서 연유되어진 것 같고 재현의 실마리를 사물의 본질에서 찾으려는 생각은 시간이 흐를수록 본질에서 점점 멀어져가는 데로 나아가는 느낌이 드는 것이 솔직한 심정이다. 한 해 한 해 나이를 먹으면 세상이라는 바다를 항해 해나가는 기술이 숙달되어져야 할 텐데 오히려 나의 경우는 그렇지 못하다.

이번 2009년도 전시의 작품 <diagram of the Light> 작업은 보는 이에게 눈에 보이지 않는 spiritual dimension 혹은 비가시적인 영역을 작품을 통해서 머릿속에 그려보기도 하고 상상해 볼 수 있기를 바라는 의도에서 제작되었다. 그런 의미에서 빛의 ‘시각적인 환영’을 그려내는 일이 나의 작업의 근간을 이룬다 할 수 있다.

삶을 시작하는 지점에서 마침표를 찍는 지점까지의 시간을 하나의 긴 선으로 그어서 볼 때, 긴 선은 무수히 짧은 시간의 단위들로 이루어져 있듯이, 무수히 작은 삶의 파편들은 단순한 도형으로써 암시되고, 화면 안에서 흩어지기도 하고 모이기도 하면서 결국은 어느 한 지점을 향하여 끊임없이 맴돌고 부유하고 있는 형상이다.

그리고, 작품 안에서 보여지는 여러 상반되는 요소들(예를 들면 평면과 입체라든지 원형과 사각, 빛과 색, 수직과 수평등)은 본인 작업의 외관상 특성이라 할 수 있는데 얼핏 보면 회화작업이기도 하면서 입체작업이기도 하고 반대되는 요소들이 한 화면 안에 어울어지는 형식을 즐긴다. 그러한 심경의 배후에는 아마도 우리들의 삶의 모습들을 화폭에 담고 싶어서인 것 같다. 화면위에서 부유하는 조형 요소들은 우리가 삶에서 끌어안고 살아가야하는 문제들-영혼과 육신, 삶과 죽음, 자연과 문명, 시간과 공간 그리고 갈망, 열정, 애환, 분노, 슬픔, 기쁨, 후회 등의 삶의 감정들-까지도 포함하는 은유이자 상징일수 있으며 그것은, 모순되고 상반되는 요소들이 한 화면 안에서 공존하고 상호 보완하면서 절충하고 때로는 격돌하고 부딪히면서 평정을 찾아가는 삶의 모습의 메타포이다.

그러한 맥락에서 볼 때 이번 전시 작품 가운데 <황금 배경 인물도>의 작업은 다소 주제에서 벗어나 보일수도 있지만, “빛”이라는 큰 주제 안에서 제작되어졌다고 할 수 있겠다.

인물도를 그려보자는 생각을 가지게 된 것 은 돌아가신 아버지 때문이다. 살아생전에 인물화 한 점 제대로 그려드리지 못하고 돌아가신지 이년이 지난 지금에야 겨우 붓을 들게 된 것에는 부모님의 사랑과 은혜로 못난 자식(?)이 개인적으로 앓고 있는 고질병 때문이다. 부모님의 초상화에 이어 가족들까지도 한사람씩 모두 화폭에 담게 되었다. 평소에 진심 어린 마음을 제대로 전달하지도 표현하지도 못하는 성격 때문에 가족들에게 이 기회를 통하여 만회를 해보아야겠다는 생각과 함께 무엇보다도 가족과의 관계회복을 통한 자신의 내면적 치유를 위하여 제작되었다는 의도가 은밀히 담겨져 있다.

덧붙여서, <황금배경인물도>에 착안하게 된 데에는 개인적으로 일본 유학 시절에 접했던 13세기 이태리의 수도승이자 화가이기도 했던 프라 안젤리코의 성모자상을 전통기법인 템패라화로 모사했었던 경험을 되살려 보고자 했던 것이기도 하다. <황금배경인물도>의 작업은 앞으로도 주변 인물들을 상대로 지속적으로 작업해 나갈 생각이다.

2009년도 개인전(빛 갤러리)

Contemporary Artists Show Individuality

[코리아타임스 2006-07-28]

Contemporary art is an all-encompassing term that covers any art being done now, whether its painting, installation art or photographs. Most galleries nowadays are eager to show off artworks by young and upcoming artists.

Gallery Kong, located in Chongno, Seoul, is now holding “Korean Contemporary Artists 5,” an exhibition of the work of five young contemporary Korean artists.

Gallery Kong President Grace Kong told The Korea Times that the five artists all embody the “Korean spirit.” The artists have worked in Korea and have been featured in galleries in New York, Paris and Switzerland.

The most well-known artist in the exhibit is photographer Kim Jung-man. Kim, who is famous for his portraits of celebrities, shows a different side with somber black and white photographs.

One of the photographs is a shot of a deserted, somewhat desolate, beach at Palm Beach in Los Angeles. Another is a striking photograph of a Korean woman walking along a tree-lined road.

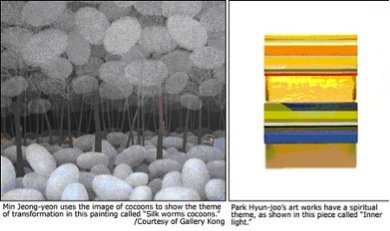

Rising young artist Min Jeong-yeon, who at 27 is already making waves in Europe, is also featured at the exhibit. Kong said Min has attracted a lot of attention from European art galleries, and is set to hold an exhibit in Germany and New York later this year.

Min’s painting “Upside down town, woman on bicycle,” shows a woman on a bicycle amid a rain of garlic cloves. This image refers to the Korean myth in which a bear ate garlic and was transformed into a man.

Another painting is “Silk worms cocoons,” in which Min uses the image of a cocoon to show the theme of transformation. “As a woman, she feels a lot of social pressure in Korean society, and this shows in her artwork. She wants to be something else,” Kong said.

Kim Soo-kang’s works are unique. At first glance, you think it’s a chalk drawing but it is actually a photograph. Making use of the “gum print” technique, the photographs take two to three days to develop.

Kim likes to elevate ordinary every day objects into works of art. In her series of photos “White Vessel,” Kim takes photos of ordinary objects she uses at home such as a rice bowl, teacups and plates. For another series, she took photos of different kinds of pojagi, the traditional Korean wrapping cloth.

Park Hyun-joo takes a more spiritual theme in her art. In “Inner light,” she reinterprets traditional Christian religious images by mounting several wooden boxes on the wall. The boxes are painted with colorful stripes on the front, but gold on the top and sides. When light hits the gold portion of the box, a soft light similar to the glow around saints and holy figures is cast on the wall.

Jeong Heon-jo’s monoprints combine embossing and drawings on a stark white background. His work shows an otherworldly image with a distinctly Asian spirit.

Referred to as a “painterly object”, Park Hyun-joo’s work, made of glass cubes has been attracting considerable attention with its two and simultaneously three-dimensional characteristics. The core of her work is none other than the light.

The light and color her piece emits are above all an outgrowth of her persistent experimentation with the materials and repetitive practicing of painting colors or putting gold foils on the cubes. Ithas a material and non-material quality in the same breath, and makes the viewers have an experience of transcending time and space.

The surface of roughly 70 glass cubes entirely occupying one side of the wall is painted in bluish color, symbolic of sacredness and infiniteness. Particularly, the light and shadow reflected out of the side mirrors has a sort of esoteric effects, blowing off some sacramental mood like in a sanctum.

When studying at theTokyo National University of Fine Arts and Musics, the artist internalized the spirituality and figurativeness of light and color through her artistic exercise copying the icons of Fra Angelico. In reading her work, especially like <Inner Light> the key word is the light such as the light from the heaven sensed in the Middle Age’s iconography and the light dissolving the boundary between matter and mind.

Over the Rainbow 2004

managed by Coreana Cosmetics at Space C

Curated by Bae Myung-ji , curator of space C

Over the rainbow전 2004.9.2-10.16

박현주는 사각의 큐브와 그 위에 덧씌워진 회화작업으로 일종의 회화적 오브제라 할수 있는 평면 설치작업으로 주목을 받아왔는데 그의 작업의 핵심은 색과 빛이다. 그의 작품에서 발산되는 빛과 색은 일차적으로 질료에 대한 작가의 끈질긴 교감과 실험, 물감을 칠하거나 금박을 붙이는 반복행위의 산물이다. 하지만 그 결과물들은 실제 시간과 공간의 초월을 경험하게 하고 시각을 무한히 확장시킨다는 점에서 물질성과 비물질성을 동시에 담보한다. 작품 제목인 내면의 빛은 비물질성 으로서의 이러한 빛의 효과를 집약한다. 이번 전시에서 한 벽면을 채운 70여개의 거울 큐브들은 그 표면이 감각적인 푸른 색조의 그라데이션으로 표현되어 있으나 측면 거울에서 반사되는 빛과 그림자는 어두움 속에서 일종의 비위적인 효과를 발휘한다. 또한 탬패라 물감의 은은한 색조로 그려진 장방형의 작품에서 네 측면을 두른 금박은 조명을 받아 반사되면서 신성한 에너지를 파생시키고 단순한 장소가 아닌 성소의 느낌을 전달해 준다. 작가는 동경예대 유학시절 프라 안젤리코의 성상화를 모사하며 빛과 색의 형상성과 정신성을 내면화해왔다. 중세 이콘화가 발현하는 천상의 빛,물질과 정신의 구분을 와해하는 숭고한 빛은 박현주의 작품을 읽어내는 키워드이다. 사각의 기하학적 규칙성과 반복적인 입방체로 대변되는 그의 작품이 미니멀리즘 조각의 즉물성과 구분되는 지점이 바로 물성을 견지하면서도 빛과 색의 신비한 일류젼을 만들어 낸다는 점이다. 이번 전시에서 그가 설치한 빛과 색의 공간은 공간의 한계를 넘어 형상화 할 수 없는 무한의 공간으로 재해석된다.

스페이스 C(코리아나 화장품 기획전시)

2004년9월3일 현실저너머 화가들의 꿈

매일경제 문화면오버 더 레인보우-스페이스 씨,

매일경제 문화면

2003년10월호 아트인컬쳐 표지그림

박현주는 르네상스 초기 성상화가 지니는 빛과 색채에 대한 시각적 경험에 천착, 이를 고스란히 밀도 있는 회화적 오브제로 형상화 한다. 그렇다고 그녀가 이러한 중세적 감성에 가까운 아이콘의 회화적 형식과 주제를 모티브로 삼은 것은 아니며 오히려 물질이 근원적 일자 로 회귀 혹은 상승하고자 한다는 신플라톤주의적 유출설을 끌어온 것에 가깝다.

외견상 작가의 작업은 물성을 특별히 강조한 모더니즘 혹은 미니멀리즘 회화의 형식주의적인 실험과 변별되기 어려워 보인다. 그러나 정통 미니멀리즘 작품들이 모든 가상적인 성격을 배제하고 최대한의 시각적인 단순성을 유지함으로써 관람자로 하여금 모호함에서 벗어나 통합적인 인상을 받게 하는데 비해 그녀의 회화적 오브제는 전통적인 회화적 수법을 견지하면서도 의도하지 않은 비의적 일류젼을 창출한다는 점에서 변별된다.

예컨대 괴테가 이탈리아를 여행하고 난뒤 색채론을 썼던 것처럼 그녀 역시 피렌체의 성 마르코 성당에서 프라 안젤리코의 성화를 보고 빛과 색채에 대한 새로운 시각적 경험을 하고는 이것을 철저하게 자신의 작업에 반영한다. 평면에 석고를 입히고 갈아내고 색을 칠하는 반복적인 행위와 사각의 측면에 금박을 덧칠하는 행위는 곧 재료와 기법에 자기 자신을 투사하는 원초적 과정이다. 물론 이번 작품은 금박의 연마작업에 근간해 이를 투영하는 새로운 방법론으로서 아크릴리라는 질료가 개입되지만 여전히 반복적인 회화적 유니트의 제작은 지속된다. 이런 회화적 반복과정은 작가로 하여금 일차적으로 물질과 교감하게 하여 자연스럽게 명상으로 유도한다.

여기에서 나와 물질이라는 주제와 객체의 경계와 구분은 사라지고 더 이상 대립 구도가 아닌 서로 침투하고 융합하는 관계가 형성된다. 작가는 이를 무아 로 명명하며 참된 자아를 찾아나가는 일종의 반성적 행위로서의 자기부정으로 받아들인다. 이는 궁극적으로 삶에 필연적으로 달라붙는 예술가로서의 근원적인 불한, 허무, 좌절, 상처등을 치유하는 순간이다.

장소특정성의 작품이 그러하듯 박현주의 작품은 작가의 내면적인 몰입의 상태를 떠날 때 완성된다. 작가에게서 떨어져 나온 작품이 특정한 공간과 조명의 부가적인 도움으로 연극적인 미적 관조의 상태에 이르게 되는 것이다. 이때 비로소 작가도 예기치 못한 빛의 파노라마적 효과. 마치 스태인드 글라스가 미묘한 빛의 뉘앙스에 따라 전혀 상이한 효과를 창출하는 것과 마찬가지의 이치를 보여준다. 그러나 그것은 치밀한 구성과 개념을 염두한 것이 아닌 이상 물질과 공간의 상호작용이 주는 시너지에 가깝다. 이를 테면 질료에 철저히 적응하고 준응하는 과정을 반복하는 지난한 여정속에서 삶이라는 간단치 않은 화두를 지속적으로 형이상학적 이데아의 빛에 투사하고 상승시키려는 작가 특유의 속성에서 비롯된 보너스 같은 것이다. 어쩌면 물성의 실험 자체를 개념화하는 시대와 격세지감을 느낄 수밖에 없는 현대미술의 맥락에서 박현주의 작업 역시 어느 형식주의적인 작업들이 가지게 마련인 메시지의 부재 혹은 주제의 공허함으로부터 자유로울 수 없어 보인다. 예컨대 영원, 자유, 평화라는 메시지의 보편성이 주는 추상적 공허함을 지울수 없는 것처럼 말이다. 물론 이러한 형식적 방법론에 입각한 작품들이 지각기능을 확장시킴으로써 의식을 풍부하게 해줄 것이라는 전제는 인정된다. 그렇지만 형식이 내용을 지속적으로 담보하는 예술의 미학적 기능은 여전히 미흡한 채로 남아 있을지도 모른다는 점은 생각해 보아야 할것이다. (미술비평 유경희)

박현주 전

2003.9.19-10.3 갤러리 인

월간 미술 11월호

전시 리뷰(미술 비평 유경희)

박현주의 회화적 오브제에는 빛이 흐른다. 사각의 오브제 내부에서 부상하여 외부로 전이되는 빛은 물리적 속성을 넘어 인간의 내면에 까지 파장을 일으키는 신비한 에너지를 지닌다. 박현주는 동경예대 재료기법 연구실에서 프라 안젤리코의 이콘화를 모사하며 빛의 형상성과 정신성을 내면화한다. 중세 이콘화가 발현하는 천상의 빛, 물질과 정신의 구분을 와해하는 숭고한 빛은 박현주의 작품 내면의 빛을 읽어내는 키워드이다. 그의 작업 속 빛의 근원은 정방형 나무상자에 입혀진 금박과 템패라 물감에 의해 표현된 다양한 색의 표정들에 있다. 특히 나무상자의 네 측면을 두른 금박은 조명을 받아 반사되면서 금속성의 번쩍임을 넘어 신성한 에너지를 파생시킨다.

사각의 틀과 그 위에 덧씌어진 부단한 회화작업은 그의 작업을 회화와 오브제의 중간지점에 놓이게 하면서 회화와 조각을 통합하는 미니멀리즘의 특수한 오브제로 인식되게 한다. 사각의 기하학적인 규칙성과 반복적인 입방체로 대변되는 박현주의 작품 내면의 빛은 일견 도날드 져드의 작품을 연상시키기도 하지만 그의 작업은 미니멀리즘이 제시하는 즉물성 대신 금박을 붙이고 연마하며 반복해서 칠하는 세밀하고도 지루한 노동의 과정으로 집약된다. 이 과정에서 작가는 자아를 소멸시키고 스스로를 작품에 순응시키며 내면의 절대자와 조응한다. 부단한 손의 놀림은 어느덧 육체와 정신, 주체와 대상의 대립을 무너뜨린다.

이처럼 작가는 내면의 빛을 통해 자아를 투사하고 반성하며 삶의 문제를 성찰한다. 그에게 빛은 자신의 내밀한 공간이 세상과 만나는 접점이다. 작가가 작업을 바라보는 이러한 방식은 미술의 객관성을 강조하고 작품에서 삶을 검열하는 서구 모더니즘 의 자기 비판성과는 엄밀히 구별된다. 박현주에게 빛은 작품 내부로부터 배어 나와 망막을 진동시키는 물질로서의 빛이면서 정신을 고양시키는 신성한 빛을 상징하고 EH한 인간의 내면을 비추어 보게 하는 영혼의 빛을 지향한다.

물질, 신성, 영혼 그 빛의 스펙트럼(스페이스 씨 배명지 큐레이터)

박현주 전 2003.9.19-10.3 인화랑

아트지 10월호 EXHIBITION Review

1.

지난 십수 년 간 박현주가 지속적으로 보여주고자 했던 것은 매우 간결한 색면들로 구성된 일련의 구성적 질서였다. 그 질서란 거의 어떤 예외적인 흐트러짐도 허용되지 않는, 규칙적인 배열과 일정한 간격에 의한 엄격하고 단정한 느낌을 주는 것이었다. 각각의 색면들의 관계를 규정하는 질서는 너무 완고해서 모든 표현행위가 종료된 이후의 안정기를 보는 듯도 하다. 어떻든 박현주의 세계는 어떤 울퉁불퉁하고 불규칙하며 우연적인 상황에 대한 최대한의 조정과 억제라는 측면에 의해 이루어진다.

부드럽거나 강한 톤의 수 개나 수십 개, 또는 일백 개 이상의 단위 색면들이 모여 만들어지는 하나의 구성체가 바로 박현주의 작품이다. 즉 박현주의 것은 언제나 각각 독립적인 수개나 수십 개의 조각인 동시에 하나다. 그렇더라도, 그것의 궁극은 ‘설치(installation)’ 보다는 각각의 단위 오브제들과 그것들의 규칙적인 배열이 만드는 구성적 질서에 입각한 회화의 변주나 확장으로 보는 것이 옳다. 박현주의 세계는 적어도 그 중요한 일부분이 색면추상의 어떤 논리적인 확장, 즉 모더니즘 회화정신의 맥락 안에 위치하고 있다.

그러나 그것만이 다가 아니다. 그의 세계를 진정한 그의 세계로 만드는 가장 근원적인 요인은 그 각각의 ‘단위-색면’들은 벽면으로부터 스스로를 구분하는 일정한 높이를 지닌, 옆으로 긴 장방형의 신체의 사방 옆면들에서 반사해 내는 빛의 화려한 변주들이다. 그 반사된 빛은 눈이 부시게 현란하며, 각 단위 색면들의 사이공간을 매우고 있다. 그 변주는 물론 각 단위 색면들의 측면 재질에서 비롯되는 것인데, 그것은 빛의 반사를 원활히 하기 위해 오랫동안 전통적인 기법으로 만들어진 금박이었으며, 최근에는 스테인레스 스틸이나 일련의 동합금이 사용되기도 한다. 여기서 반사되는 빛의 변주들은 단위 오브제에 조사된 빛의 질과 양, 원근, 각도를 반영하면서, 그리고 벽 위에서 단위 색면들의 강렬한 원색들과 뒤섞이면서 경이로운 시각적 효과를 만들어낸다. 그 전체가 만들어내는 것은 마치 넘실거리는 황금빛, 또는 순은색의 바다와 그 사이에서 규칙적이고 기하학적으로 돌출된 색채의 섬들 간의 강렬한 상호작용이다. 이렇듯, 실체와 비실체, 오브제와 탈오브제, 색과 빛 같은 상충하는 질서의 공존이 조율해내는 변증은 일상에선 경험하기 어려운 경이롭고 풍요로운 것이다.

박현주의 빛은 단번에 우리를 사물의 너머, 초현실의 문턱으로 안내한다. 그 빛은 돌출된 입방체와 강렬한 채색의 주변에 낮게, 그리고 조용히 자리하면서 그것들의 물성을 완화하고, 어떤 ‘사유적인’ 차원을 매개한다. 그렇더라도, 이 빛은 예컨대 렘브란트의 천정을 뚫고 쏟아져 들어오는 강렬한 직사광선과는 다르며, 사물 또한 그 구제를 기다리는 융통성 없는 가련한 3차원인 것만도 아니다. 빛은 사물을 부드럽게 스치고, 사물은 빛의 작용을 매개한다. 여기서 빛이 진정으로 초월적일 수 있는 것은 그 빛이 사물에 의해 육화된 것이기 때문이다. 그 안에는 일정부분 사물화된 빛, 사물의 흔적을 지니고 있다. 각 단위 색면들의 구성들 또한 그 자체로서도 매력적인데, 그 매력은 빛의 개입에 의해 전혀 퇴색되거나 둔화되지 않는다. 물성은 후퇴하지 않으면서 오히려 어떤 초현실의 기반이 된다. 사물은 빛의 동반자가 되고, 빛은 색의 수준을 공유하고 있다. 이는 어쩌면 그의 동경대학 재학시절 그가 속했던 아틀리에에서 서구의 옛 거장들, 예컨대 프라 안젤리코의 성모상 등을 통해 빛에 대한 새로운 통찰이 가능했다는 사실과 관련이 있을 것이다 : “ 성상의 모사실습거치면서 …나는 점점 더 적극적으로 회화에서의 빛의 효과에 매달리기 시작했다.”(박현주)

2.

연구 끝에 그는 빛을 회화의 세계로 초대해 들이는 한 방식을 발견했는데, 바로 회화적 질서를 교란하지 않을 뿐 아니라, 더욱 지지하는 것으로서 빛이 작용하도록 하는 것이다. 반사광의 어른거림이 하나의 강렬한 원색을 에워싸도록 함으로써, 색과 빛이 동등한 차원으로 하나의 평면 위에 공존하도록 하는 방식이 그것이다. 정술했듯, 여기서 ‘빛(光)은 사물의 표면에 반사되면서 그 사물의 색(色)으로 육화(incarnation)된다. 이 빛은 사물의 기억과 흔적에 의해 끊임없이 조율되는, 일종의 ’색 반사‘라 할 수 있는 방식으로, 이는 예컨대 댄 플라빈(Dan Plabin) 같은 작가의 경우처럼 외부의 전기적 요인에 기대지 않으면서 빛을 색화할 수 있는 매우 시적인 방식이 아닐 수 없다.